The Make in India initiative was launched on 25 Sep 2014 while The Atma Nirbhar Bharat policy was unveiled on 12 May 2020. In both these programs, Defence Manufacturing occupies major space. While the overall objective of the Government of India is to increase the share of manufacturing in the GDP to 25% by 2025 by focusing on 25 different sectors including Defence, attention is undoubtedly on Defence due to the sheer size of defence imports every year. As per the latest SIPRI report, India accounted for 11% of the total global arms imports between 2018 to 2022, even though the share of expenditure on defence procurement through imports has reduced from 46% to 36.7% during this period. In the 2022-23 budget, the objective of 68% of capital procurement for defence from indigenous manufacturers was spelt out, which is supposed to be further enhanced to 75%, as per the Hon’ble RM speaking in the GIS conclave in Lucknow. Clearly, such policy announcements open up massive opportunities for the defence manufacturing sector.

The technology involved along with R & D

Weapon systems and platforms required and procured by the defence forces have always been based on the prevailing cutting-edge technologies, in fact, a convergence of top-notch technologies. Thus, a fighter aircraft employs state-of-the-art aeronautical engineering, jet engine technology, avionics, sensors, fly-by-wire technology, precision-guided munitions, Surveillance and Electronic Warfare technologies etc. An Armoured Fighting Vehicle or a Tank is a system of systems integrating mechanical engineering (power pack), Armament Technology, Fire Control System, Sighting System, Gun Control System, Communication System, NBC Protection etc. In all such weapon systems or platforms, prowess in Metallurgy, Rubber Technology, Control systems etc is a must. It is difficult, if not well nigh impossible, for a single manufacturer or entity to have all the capabilities required in producing or integrating a particular defence equipment. For example, the Su-30 MK I aircraft manufactured by Hindustan Aeronautics Limited (HAL), under license, has systems and components supplied by 14 manufacturers in six nations.

In fact, it will not be an overstatement to say that the gamut of defence equipment encompasses the whole range of technologies which mankind has invented and more. Thus, the enormity of the task of being Atma Nirbhar or self-reliant in the manufacture of Defence Equipment for a country like India should not be lost in the grandeur of policy statements. In fact, if the nation can move from the estimated self-reliance level of 25 – 30%, as of now, to a figure of 75 – 80%, the goal should be considered as achieved. The challenge is indeed daunting for a nation whose traditional strength is not manufacturing and can only be tackled by the steady acquisition of incremental defence manufacturing capabilities. How this Make in India and Indigenous Defence Manufacturing can be facilitated and speeded up is something worth examining.

One critical factor in the development of new technologies and their employment in the design and manufacture of defence equipment is the investment in R & D. In terms of percentage of GDP, India’s spending on R & D is estimated to be amongst the lowest in the world. In 2022, India spent 0.65% of GDP on R & D, which is lower than the BRICS nations and much lower than the world average of 1.8%. Countries like US and China reportedly spend about 2.8 % to 3% of their GDP on defence R&D. Israel, a major exporter of defence technologies spends almost 6% of its GDP on R&D. China is continuously increasing its R&D investments for the last 25 years and is expected to surpass the US by 2026. If we account for the fact that the GDP of the US/China is 6 to 8 times bigger, one can comprehend the enormity of asymmetry in the spending on Defence R & D.

The number of scientific papers published in international journals and the technological infrastructure thus created, due to the focus on R & D, leads to innovation and development of new technologies. An indicator of its success is also the number of Patents granted; it is here that the asymmetry gets further skewed as India has a minuscule number of patents granted over the years, less than 1% of the countries mentioned. The corollary is that increase in R & D budget is an indispensable component of the strategy which is required to be put in place for achieving a higher self-reliance quotient. Overall, if we can spend about 2% of GDP on R & D, it will be a big boost to our quest of being Atma Nirbhar. However, the reality is that today the whole defence budget has got compressed to just about 2% of GDP. Thus, to achieve the indigenous manufacturing targets, there is no option but to look towards private sector R & D and manufacturing as well as foreign investments and collaborations. A welcome development, announced recently by the Government is the setting up of a National Research Foundation (NRF) with a corpus of Rs 50,000 crore for R&D over five years. The bill will be introduced in Parliament and will foster a culture of R&D in Universities. Colleges, Research Institutions and R&D labs.

Promotions and Incentives

Defence manufacturing is not only a function of national economic resources allocation, R&D budget / NRF but is also based on the industrial base existing in the country. If the base is sound with overall strengths in technology, defence manufacturing gets facilitated. This industrial base or ecosystem can involve both the public sector and private sector, wherein the respective strengths need to be synergized. However, the private sector differentiates itself by its overarching profit motive. Since, the design, development and manufacture of defence equipment require long gestation periods, industry, particularly the private sector, needs to be suitably incentivized.

Also Read: Indian defence production- towards self-reliance

Defence Manufacturing also requires skilled human resources. Ie Engineers, Scientists and Technicians along with Academia to impart the requisite technical skills. Further, it requires suitable civil and technical infrastructure and an integrated ecosystem for defence manufacturing to flourish. Even after all this is in place, it takes years, if not decades, for R & D to succeed, prototypes to be made and tested and the manufacturing line to be set up with all the supply chains. Thus, the cost of achieving self-reliance can be exorbitant and may have time penalties also. The public sector efforts in defence manufacturing have to be complemented by the Private sector so as to increase the indigenous content. There has to be hand-holding of innovators and system integrators; ideally, a Public- Private Partnership model has to be put in place where part funding of the private sector is enabled and their costs amortised. Collaboration and not competition amongst agencies involved in defence projects has to be encouraged.

As far as Foreign Direct Investment is concerned, the Government has been steadily increasing the FDI limits in the defence sector which is presently at 74% (automatic route) and 100% (Government route) to make the Indian defence industry an attractive investment destination. Foreign OEMs can avail cost advantages of manufacturing in India and export to other countries in the region. Since technology infusion requires the industry to collaborate with foreign OEMs; Indian and foreign OEMs should set up Joint Ventures and Special Purpose Vehicles which include both, a manufacturing and an R&D element.

The government has also started a Production Linked Incentive scheme, ie PLI to boost domestic manufacturing and cut down on import bills. It gives incentives to companies for incremental sales from products made in domestic units. At present the scheme targets labour-intensive sectors, with the drone and drone components sector being the only sector, amongst 14 sectors, with a semblance of defence connect. As the Government plans to add more sectors to the PLI scheme, it will be worthwhile to consider PLI in a few carefully chosen defence manufacturing sectors also, say assemblies and modules which are being imported today. It will incentivise foreign investments and collaboration also.

Infrastructure and environment of ease

Some of the policy initiatives of the Ministry of Defence, in recent years, give rise to optimism that the private sector is being encouraged to become an integral and important part of the defence industrial ecosystem. An initiative like the Strategic Partnership model was introduced in the 2016 edition of the DPP and notified in May 2017. This envisages the establishment of long-term strategic partnerships with Indian entities through a transparent and competitive process, wherein they would tie up with global Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEMs) to seek technology transfers to set up domestic manufacturing infrastructure and supply chains.[5] This can give a big boost in the manufacture of submarines, aircraft, helicopters and armoured vehicles and is a step in the right direction. Initiatives like IDEX, ie Ideas for Defence Excellence, launched in 2018, also hold huge potential by integrating Startups, MSMEs, R&D establishments, Innovators and Academia in the defence ecosystem, while providing them grants/funding and other support. It has already manifested in some startling successes, including the 1000 drone swarm display during RD 2022 and the manufacture of very high-resolution cameras.

Setting up of two Defence Industrial Corridors in UP and Tamil Nadu, announced in 2018-19, is also a step in the right direction. The aim is to attract foreign investments of up to Rs 20000 crore by 2024-25. The respective state Governments have also published Defence and Aerospace policies to attract investments. Already, significant progress has been made; 108 Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) have been signed with Industries in UPDIC having a potential investment of Rs 12,191 crore (investment of Rs 2445 crore made) while in TNDIC, MoUs with 53 industries for potential investment of Rs 11,794 crore has been made (investment of Rs 3894 crore made). Perhaps more such corridors can be set up in industrialised states like Maharashtra and Gujarat. What is also of importance is that single window clearance is facilitated, licensing simplified (validity already increased from 3 to 15 years), manufacturing of more parts delicensed and regulatory mechanisms eased out.

Also Read: Defence production – time to go back to square one?

As per the PIB release of 19 May 2023, Defence production has crossed Rs 1 lakh crore mark for the first time ever in 2022-23. A number of policy reforms have been undertaken to achieve the objective of ease of doing business, including the integration of MSMEs and start-ups into the supply chain. There is almost a 200 per cent increase in the number of defence licenses issued to the industries in the last 7-8 years.

However, it is felt that there is a need for a centralised agency to formulate, coordinate, and monitor the R&D and production of defence systems in India. The R&D and technology development today is fragmented with Defence Forces making a wish list in the form of Long Term Perspective Plan (LTPP) while the DPSUs frame the Technology Perspective Capability Roadmap (TPCR) and the DRDO makes the Long Term Integrated Perspective Plan (LTIPP) based on the Services requirement. There is no single agency to coordinate and integrate all these plans. An institutionalized arrangement, in the form of a Central Agency, needs to be put in place which should have members from Services, DRDO, Ministries of Defence and Science & Technology, PSUs, Private Industry, Scientists, Academia and Business Chambers. This Agency should continuously collate all the inputs, requirements, technological capabilities, gaps and opportunities. The LTPP of the Services should then be discussed threadbare by the Board Members of this Agency while formulating a five-year plan with a firm, prioritized budget and timelines.

International markets

It is important that in addition to equipping the national defence forces, the defence industry should also be able to export military hardware to friendly foreign countries. Success in exports enables the scaling up of production and achieves economies of scale by the entire defence manufacturing ecosystem. In addition, Defence exports provide military and diplomatic leverage and are an important source of revenue generation to support internal requirements. This leverage is an important consideration for an emerging power like India to retain its edge in its strategic sphere of influence. As of now, India is ranked within the top 25 countries in defence exports but its share is actually abysmally low.

India is now steadily increasing its domestic defence manufacturing capabilities, while simultaneously increasing exports of the hardware to friendly foreign countries. In fact, since 2016-17, defence exports have already seen an almost tenfold impressive increase from Rs 1521 crore to Rs 15920 crore in 2022-23. The Government has set a target of reaching defence exports of Rs 35000 crore by 2024-25. Notable export deals include the supply of 155 mm artillery guns and Teevra 40 mm guns to the Indonesian Navy. There is a $ 250 million contract for the supply of Pinaka missiles to Armenia. India is also finalizing missile deals with Indonesia, following the $ 375 million Brahmos missile agreement signed with the Philippines last year. As part of foreign collaborations, India will be manufacturing aerostructures for Boeing’s AH-64 Apache helicopters There is a deal with Airbus Defence and Space to produce C-295 medium lift transport aircraft. During the recent visit of the PM to the US, there was an announcement of procuring 31 Predator 9 QB drones which is accompanied by the establishment of a global MRO set up in India which will be a harbinger of exports in future.

In fact, arms deals in the international market are also an important indicator of the degree of self-reliance a nation has achieved in the realm of defence. As of now, there is no reliable way to determine the overall degree of indigenisation in defence since each indigenously manufactured system may have a number of imported components. A simpler way to determine the Index of Atmanirbhrta in Defence could simply be the ratio between the Export and Import of defence equipment. As an illustration, the Indian arms exports in 2022-23 were 15920 crores while imports were Rs 40,840 crores as per the Hon’ble Minister of state for Defence. However, if the figure is to be based on the SIPRI report of Global arms trade of $112 billion and India’s share as 11%, the import would be of the order of Rs 100 Lakh Crore. Depending upon which figure is taken, the Atma Nirbharta index would be between 0.16 and 0.39. Of course, it is set to improve in future due to an emphasis on local manufacturing and exports.

Change in mindset

It is felt that no amount of R&D or policy focus would lead to desired outcomes in defence manufacturing unless it is accompanied by a significant change in mindset. To illustrate, two cases are being enumerated. Project ARJUN for the indigenous armoured fighting vehicle was conceived in 1972 and DRDO was tasked in 1974. Design by CVRDE was finalized between 1983 and 1996. The production began in 2009 with a 1400 HP German MTU engine and RENK transmission. Although its top speed was high, 72 Km/hour, its weight had burgeoned to an unwieldy 62 Tons. There were operational issues and Army ordered only two regiments. The Mk II version added ERA panels and the weight increased further to 67 Tons. The design and development period took so long that the final product, even with imported content had issues. Due to economies of scale not kicking in, the spares back up and thus maintenance of the limited inventory has also become a problem.

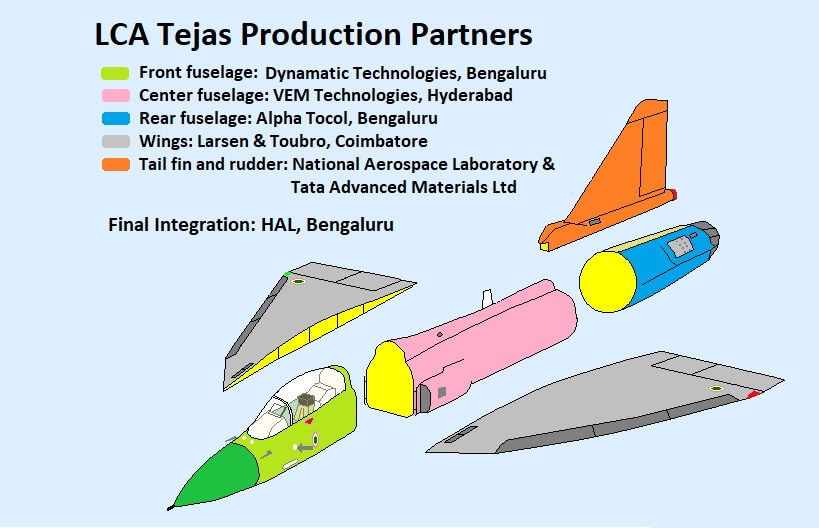

The next case is of Light Combat Aircraft (LCA) program started in the 1980s with Aeronautical Development Establishment (ADE) tasked to design a single-engine, light multirole fighter aircraft to replace the MIG-21s. HAL was to manufacture this LCA termed Tejas. Kaveri Gas Turbine engine was to power this LCA and Gas Turbine Research Establishment (GTRE) was tasked with developing this 10,000 kg thrust engine, a very complex technology, requiring prowess in metallurgy of the highest order because of extremely high temperatures. Not unexpectedly, the Kaveri engine failed in technical requirements and was delinked from the project in 2008. LCA Tejas then took on board the imported GE 404 engine and initial clearance for the flight was given in 2011, with final clearance given in 2019. Now during the Prime Minister’s recent visit to the US, there is a GE-HAL deal for a GE-414 jet engine which will power LCA Tejas, the Generation 5 fighter jet.

Lessons learnt?

Firstly, the planners for any futuristic weapon system/platform must refrain from formulating an eclectic mix of Qualitative Requirements. Perhaps, there is no weapon system or equipment in the world which is best in class in all possible parameters. Thus, the focus should be on the Optimal mix of technical specifications which will give a realistic design challenge to the Developing Agency.

Next, the Developing Agency, or a Composite Expert Body, as suggested earlier, should carry out a SWOT analysis of the challenges in design and manufacture. Technologies, where adequate indigenous capability is not available and which require large capital investments along with estimated time penalties, should not be targeted for local design and development. Instead, Joint Ventures with foreign OEMs for the same should be encouraged with outright import being the last option.

It should be understood that no nation can ever be 100% self-reliant in all the state-of-the-art technologies with the rapidly changing operational landscape and disruptive technologies. Only five countries in the world produce jet engines as of today. SU-30 Mk I, manufactured by HAL under license, has systems and components supplied by 14 manufacturers in six nations. Many manufacturing challenges become insurmountable if adequate know-how and prowess in metallurgical engineering is not there and this is one area which requires tremendous capital investment.

Even if the technological capability is there but economies of scale are not favourable, it may be better to join global supply chains, the earlier the better.

The private sector has to be encouraged and provided a level playing field. Transfer of Technology (ToTs) available with PSUs, whenever feasible, should be transferred free of cost to private sector manufacturers. Handholding by the Government, especially for MSMEs is imperative. Unlike the FICV program, which started in 2006 and closed 15 years later where big industry would have absorbed losses but MSMEs would have been devastated; it should not happen again.

Conclusion

Self-reliance in defence manufacturing is a strategic imperative for India. As a regional Indo-Pacific power, India’s dependence on imports is a critical vulnerability. India’s defence manufacturing, although poised on a transformational cusp, has an arduous journey ahead before it can enter the league of self-reliance. Many of the impediments of the past, which retarded progress, are being addressed. The Government has set ambitious targets for indigenization and its recent policies are aimed at revitalizing this sector with a focus on innovation, technology development, exports, enhancing existing capacity and improving efficiencies in defence manufacturing. The entry of the private sector also bodes well for the future. However, there are still areas where the pace of change could be accelerated. The emergence of India as a defence manufacturing hub not only to meet its own security requirements for India but for the entire region will depend on the nation’s ability and inclination to walk the talk in ensuring that its progressive policies are implemented in both, letter and spirit. Only, after the simultaneous success of all initiatives listed, Defence Manufacturing can firmly set itself in the fast lane and occupy the pole position in the Indian Manufacturing ecosystem.