“Theirs was a large world in which peoples and cultures moved and mingled, unhindered by boundaries of the kind erected much later by imperial powers. From one island to another they sailed to trade and to marry, thereby expanding social networks for greater flows of wealth.”

Epeli Hau’ofa

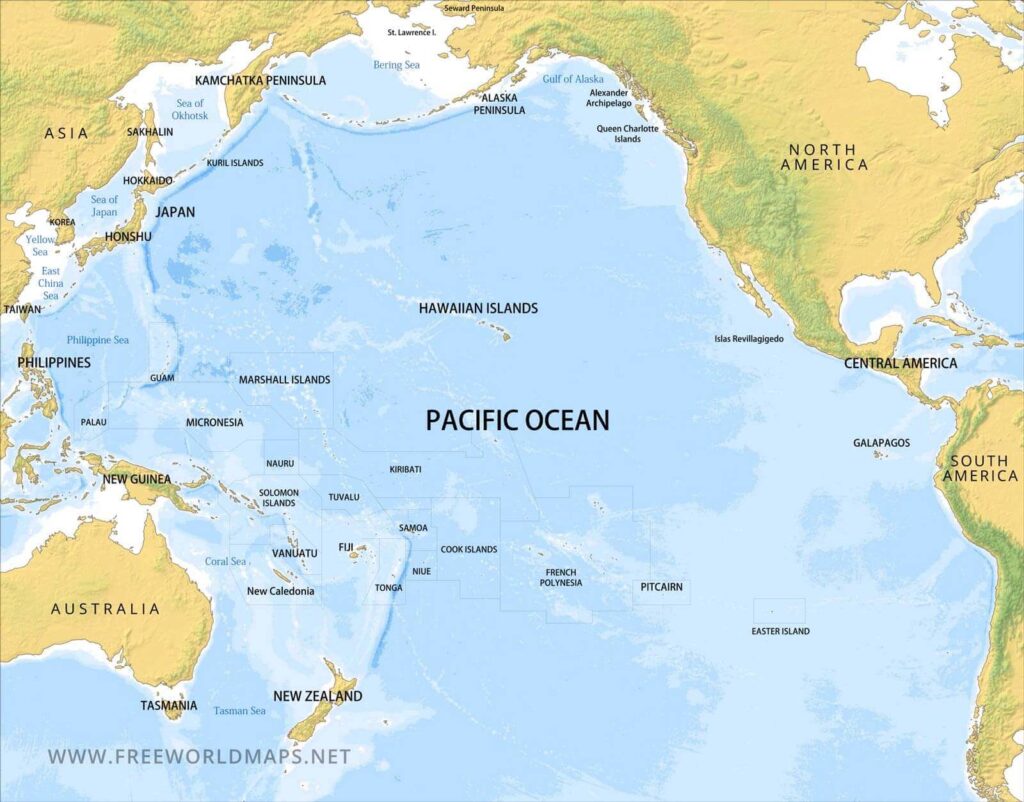

Changing Naval Power in the Pacific

In 1520, after successfully passing through the stormy Straits of Magellan, the Portuguese navigator Ferdinand Magellan encountered a vast and calm ocean. He called it Mar Pacífico, which means “peaceful sea” in Spanish. Little did he know that four centuries later, the Pacific Ocean would see the fiercest and bloodiest naval battles ever fought on earth.

The First World War

During World War I, the Allied forces swiftly sought to seize control of German colonies in the Pacific region. Germany’s principal base was in Qingdao, China, with additional territories in Micronesia, New Guinea, and Samoa. Upon the declaration of war in 1914, the Allies promptly occupied these areas.

The primary German naval force, the German East Asia Squadron, was commanded by Vice Admiral Maximilian von Spee. Aware of the squadron’s isolation and vulnerability, Spee departed from Qingdao, attempting to traverse the Pacific while engaging enemy ships with the goal of returning to Germany. The squadron achieved victory off the coast of Chile by sinking two British vessels. However, this success was short-lived. The squadron’s reliance on a limited number of coaling stations and the absence of global support rendered it susceptible to defeat in the war. The Royal Navy intercepted and annihilated Spee’s squadron at the Battle of the Falkland Islands in December 1914, far from the Pacific. This defeat marked the end of Germany’s naval presence in the region and underscored the necessity for a robust global support network, a challenge that was addressed in subsequent conflicts in the region.

Colonial Shifts and Naval Landings in Micronesia and Melanesia

The Allies encountered minimal resistance in their efforts to capture German colonies in the Pacific. Micronesia, encompassing the Marianas, Carolines, and Marshall Islands, was seized with little opposition by the United States. Similarly, over 1,000 New Zealand troops, supported by Australian and French naval forces, occupied German Samoa without resistance.

In Melanesia, the Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force (AN&MEF) arrived in German New Guinea in September 1914. The Australians faced some resistance at the Battle of Bita Paka but prevailed, leading to the surrender of the entire German colony. These early land-and-sea operations exemplified nascent forms of amphibious warfare, which later became significant in the Pacific during World War II. They demonstrated the capacity of naval forces to assist ground troops in capturing remote island territories. These initial landings were less challenging than the heavily fortified battles the Allies confronted on these islands three decades later, highlighting the substantial transformation in the Pacific conflict.

The Pacific War

The Pacific War, also referred to as the Pacific Theatre, represented the most extensive area of conflict during World War II, encompassing the Pacific and Indian Oceans and parts of Asia. The primary confrontation was between Japan and the Allied forces, particularly the United States. Although hostilities between Japan and China had commenced in 1937, the Pacific War is considered to have begun with Japan’s assaults on U.S. and British territories on December 7-8, 1941. Japan’s strategic objectives included establishing a vast defensive perimeter and acquiring critical resources in Asia.

This conflict differed markedly from World War I in the Pacific region, which primarily involved the swift and unopposed seizure of German colonies. Three decades later, these islands became the sites of intense combat, including some of the largest naval engagements in history. This transition from minor colonial skirmishes to a comprehensive war was driven by expanding global ambitions, shifts in geopolitical power, and advances in naval technology and strategy.

Prior to World War II, the United States had already initiated preparations for potential threats from Germany and Japan by developing a formidable naval presence in the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. This strategic initiative began in the late 19th century when the U.S. emerged as a power in the Caribbean and Pacific after the 1898 Spanish-American War. By acquiring territories such as the Philippines and Hawaii, the U.S. secured significant military and trade positions in the Pacific, which would be beneficial in case of future conflicts in the region.

During the interwar period, several naval treaties were established, including the Five-Power Treaty of 1922 and the London Naval Treaty of 1930. These agreements aimed to establish a hierarchy of naval power, positioning the U.S. and Great Britain at the forefront, with Japan in a secondary position with fewer ships. Although these treaties were intended to prevent an arms race, they inadvertently created an imbalance. Japan, which was experiencing rapid growth, sought to alter this dynamic. The U.S. responded by constructing numerous ships for a two-ocean navy, illustrating that national objectives often transcend diplomatic agreements. The treaties failed to avert war; instead, they set the conditions for it, where traditional naval strategies were tested by new circumstances.

During the Pacific War, the Allies, primarily the United States, devised a strategy to defeat Japan. They divided their command into two principal sectors: the Pacific Ocean Areas, under the leadership of Admiral Chester Nimitz, and the Southwest Pacific Area, commanded by General Douglas MacArthur. Although the Allies prioritised defeating Germany, a distinct strategy was required in the Pacific to counter Japan’s rapid expansion. This necessitated combat approaches, including aircraft carriers and amphibious landings.

The Second World War

The Pacific War commenced with surprise attacks by Japan on December 7-8, 1941. These assaults targeted the American naval base at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii and U.S.-held territories in the Philippines, Guam, and Wake Island. This offensive also impacted British and Dutch colonies, establishing a broad Japanese defensive perimeter across East and Southeast Asia and the Pacific Ocean.

In response, the Allies, led by the United States, divided the command of their forces between the Joint Chiefs and the Western Allies Combined Chiefs of Staff. Admiral Chester Nimitz was appointed to lead the Pacific Ocean Areas Command, which encompassed most of the Pacific Ocean and its islands. General Douglas MacArthur was designated to command the Southwest Pacific Area, which included the Philippines, Australia, and New Guinea. The Allies employed a dual strategy to achieve their objectives in the war. MacArthur aimed to reclaim the Philippines and sever Japan’s supply lines. The United States Navy sought to bypass heavily fortified islands in favour of capturing smaller, less-defended ones closer to Japan. Both the Army and Navy executed their respective strategies.

“The most stunning and decisive blow in the history of naval warfare.”

—John Keegan, describing the Battle of Midway

A pivotal moment for the Allies occurred in mid-1942 when Japan’s expansion was halted following American victories at the Battle of the Coral Sea and the Battle of Midway. The Battle of Midway was particularly significant because it thwarted Japan’s plan to annihilate the U.S. Pacific Fleet carriers. American intelligence and air power succeeded in sinking four Japanese carriers, enabling the Allies to transition from a defensive to offensive stance.

The Philippines: A Strategic Location

The Philippines was strategically important to both the United States and Japan. Following the Spanish-American War, the U.S. established substantial military bases in the Philippines, including the Subic Naval Base and Corregidor Island, intended as a formidable fortress at the entrance of Manila Bay. Japan’s surprise attack on the Philippines on December 7-8, 1941, coincided with the attack on Pearl Harbor, forming a crucial component of Japan’s strategy to dominate the Pacific. Subic Bay served as a major repair and supply hub for ships, making it a key target for the US. To prevent Japanese utilisation, the U.S. military scuttled the Dewey Drydock at Mariveles Bay in April 1942. The loss of the Philippines represented a significant setback for the Allies, necessitating General Douglas MacArthur’s retreat to Australia, where he vowed to return and liberate the country.

The Battle of Leyte Gulf: A Major Naval Engagement

The Allied forces commenced the recapture of the Philippines by invading Leyte in October 1944, a move of military and political significance in the region. This action aimed to sever Japan’s access to essential oil and rubber supplies in Southeast Asia and fulfil General MacArthur’s promise to liberate the U.S. territory. In response, the Japanese Navy initiated a major counteroffensive known as the “Sho-1” plan, intending to entrap and annihilate the American fleet in the Leyte Gulf. Three Japanese forces converged to engage the Allied fleet. Vice Admiral Jisaburo Ozawa’s fleet, comprising four aircraft carriers but few planes, was tasked with diverting Admiral Halsey’s formidable Third Fleet.

The Battle of Leyte Gulf, which occurred from October 23-26, 1944, was the largest naval battle in history, involving over 200,000 naval personnel. Halsey pursued Ozawa’s fleet, leaving the primary invasion force in the Leyte Gulf vulnerable to attack. This resulted in the intense Battle of Samar, where a small U.S. force successfully repelled a significantly larger Japanese fleet. Japan suffered a catastrophic defeat, losing 30 ships, including four carriers and three battleships in the battle. This loss was devastating for Japan’s economy. With its industrial capacity impaired and fleet decimated, the Japanese Navy could no longer mount offensive operations in the Pacific theatre. This defeat was instrumental for the Allies in continuing their advance and reclaiming the Philippines.

The Battle of Leyte Gulf is recognised as the largest naval engagement in history, encompassing an area exceeding 100,000 square miles of ocean.

Melanesia: Guadalcanal and the Gateway to Australia

In 1942, the Solomon Islands in Melanesia emerged as a pivotal theatre of conflict during World War II. Early in the year, Japanese forces occupied the islands and commenced the construction of naval and air bases, intending to use these installations to threaten the supply routes connecting the United States, Australia, and New Zealand. In August 1942, the Allied forces launched a counteroffensive against the Axis powers, deploying troops on Guadalcanal, Tulagi, and the Florida Islands to seize an airfield under Japanese construction.

The ensuing battle for the island and its surrounding waters persisted for six months and was exceedingly arduous. The airfield, subsequently named Henderson Field, became the focal point of the strategic operations. This conflict underscored the critical importance of controlling the land, sea, and air domains. The Allies required maritime dominance to sustain their forces on the island and aerial superiority from the Henderson Field to shield their naval assets from Japanese aircraft.

The War in “Iron Bottom Sound”

The waters surrounding Guadalcanal were the sites of numerous intense and disorienting naval engagements. This area earned the moniker “Iron Bottom Sound” because of the numerous ships that were sunk there. These battles served as testing grounds for the naval tactics and technology of the United States.

The Battle of Savo Island, which occurred on August 8-9, 1942, represented a significant setback for the Allies. Japanese cruisers, leveraging their superior night-fighting capabilities, succeeded in sinking four Allied heavy cruisers in less than an hour, highlighting the U.S. disadvantage in nocturnal engagements. However, the United States rapidly advanced its technological capabilities, in subsequent battles, such as the Battle of Cape Esperance and the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal, U.S. vessels employed radar technology to detect Japanese ships before visual contact, enabling pre-emptive strikes. This technological advancement contributed to levelling the playing field. The naval battle of Guadalcanal, spanning November 12-15, 1942, was particularly costly, with significant losses of ships and aircraft on both sides.

The Allied victory at Guadalcanal in February 1943 marked a crucial turning point in the Pacific War. It represented the first major triumph for the Allies, effectively halting the Japanese expansion. The conflict was gruelling, with substantial personnel and materiel losses on both sides. The Allies incurred approximately 7,100 casualties, along with the loss of 29 ships and 615 aircraft. Japan suffered the loss of 31,000 personnel, 38 ships, and 683 aircraft during the war.

The inability of Japan to replenish its lost ships and skilled pilots underscored the necessity of controlling the land, sea, and air domains rather than relying solely on naval power.

Micronesia and Polynesia: The Theatre of “Island Hopping.”

Following the victory at Guadalcanal, the Allies adopted a novel strategy known as “island hopping” to advance across the Central Pacific. Rather than engaging every island, the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps strategically selected key islands for capture, establishing bases and airstrips. This strategy aimed to position B-29 bombers within striking distance of Japan while circumventing heavily fortified enemy defences. The remaining islands were effectively isolated from the supply lines. The strategic approach of “island hopping” conserved resources, minimised casualties, and facilitated the rapid advancement of Allied forces towards Japan. It diverged from conventional land battles and subsequently influenced future U.S. military strategies.

Truk Lagoon: The Neutralization of a Fortress

Truk Lagoon, located in Micronesia, served as a formidable Japanese stronghold. Constructed with airfields and submarine bases, it was highly fortified and earned the moniker “Gibraltar of the Pacific,” becoming a principal naval base after Pearl Harbor. However, the U.S. Navy opted against a direct invasion of the island, instead, on February 17-18, 1944, they executed Operation Hailstone, a significant air and naval offensive under the command of Admiral Raymond Spruance. This surprise assault resulted in the sinking of over 50 ships and the destruction of numerous aircraft, effectively neutralising Truk’s role in the war and impairing Japan’s logistical capabilities in the Pacific Ocean.

The decision to circumvent and neutralise the fortress underscored the efficacy of carrier-based aircraft against a stationary fortified target, establishing a pivotal strategy in the latter stages of the war.

Tarawa: The High Cost of Direct Assault

While the U.S. strategy involved circumventing enemy strongholds, certain direct assaults were imperative to secure strategic locations. The Battle of Tarawa in the Gilbert Islands (Polynesia) in November 1943 exemplified this necessity, albeit at a significant expense. Operation Galvanic aimed to capture the airstrip on Betio Island to facilitate the advance towards the Marshall Islands and, subsequently, the Marianas Islands. It was one of the most intense and bloody battles of the war. The Marines encountered substantial obstacles, including shallow reefs that impeded landing craft and necessitated wading under heavy fire. The Japanese defenders, who were entrenched in over 500 fortified positions, mounted fierce resistance. Initial naval and aerial bombardments proved ineffective, resulting in 75% casualties among the first wave of marines. The battle persisted for 76 hours, culminating in over 1,000 U.S. fatalities, while all Japanese defenders perished in the battle. Despite the considerable human toll, the victory was pivotal because the captured airstrip supported subsequent operations in the Marshall Islands.

The Battle of Tarawa imparted critical lessons in refining amphibious tactics and pre-landing bombardment, which were applied in later campaigns to mitigate losses against a unyielding adversary during the Pacific War.

The Aleutian Islands: The Unlikely Front

The Aleutian Islands campaign, spanning June 1942 to August 1943, was the only World War II campaign conducted on North American soil. In June 1942, the Japanese Navy occupied the islands of Attu and Kiska, anticipating that control of the Aleutians would thwart a potential alliance between American and Soviet forces and preclude a future assault on Japan via the Kuril Islands. Some historians suggest that the invasion also aimed to divert the U.S. Pacific Fleet’s attention from Midway Atoll, as both operations were orchestrated by Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto.

Despite the campaign’s objectives, it proved to be a minor event with a negligible impact on the war’s outcome. The islands’ isolation, coupled with severe weather conditions and challenging terrain, rendered military operations exceedingly difficult and costly for both. The campaign resulted in 1,500 American casualties, a substantial cost for a region of limited strategic significance during the Pacific War.

The Battle of the Komandorski Islands: A Unique Surface Engagement

Although the Aleutian campaign was arduous and strategically insignificant, it featured a notable naval engagement: the Battle of the Komandorski Islands on 27 March 1943. This battle was one of the last instances of daylight naval warfare without aerial support. A U.S. cruiser and destroyer group intercepted a Japanese convoy that attempted to resupply the Aleutian garrisons. Despite being outnumbered, American forces, including the heavy cruiser USS Salt Lake City, engaged the Japanese fleet in a protracted gun battle. The Japanese achieved a tactical victory by damaging American vessels. However, Admiral Hosogaya, the Japanese commander, committed a critical error by retreating due to the anticipated threat of an American air assault that never materialised, thereby granting the U.S. Navy a strategic victory. Following the battle, Japan ceased efforts to resupply its Aleutian garrisons via surface ships, opting for submarines instead.

The admiral’s decision to retreat, driven by the perceived threat of air power, underscored a significant shift in naval strategy, highlighting the increasing importance of carrier-based aviation, even in the absence of direct aerial engagement.

The Ryukyu Islands: The Final Act

The Ryukyu Islands, particularly Okinawa, represented the Allies’ final major objective before the invasion of mainland Japan. Situated just over 160 miles from Japan, Okinawa was of critical importance and served as a substantial base for the Operation Downfall. The Battle of Okinawa, which spanned from April to June 1945, was the largest and most costly operation in the Pacific War, involving a million combatants and resulting in approximately 3,000 fatalities daily.

The Fury of the Kamikaze

The Battle of Okinawa posed a formidable challenge to the U.S. Navy, which was tasked with safeguarding a large and vulnerable force from numerous Japanese kamikaze attacks during World War II. Aware of the Allies’ formidable firepower, Japanese naval commanders resorted to these desperate yet effective tactics to impede the invasion. The kamikaze assaults represented a novel and potent form of warfare, resulting in the sinking of 32 U.S. ships and damage to many others.

Operation Ten-Go: The End of the Battleship Era

The battle concluded with Operation Ten-Go, which marked the final mission of the Japanese battleship Yamato, the largest and most heavily armed battleship ever constructed, symbolising the pinnacle of battleship design. In April 1945, Yamato and a small escort embarked on a one-way mission to Okinawa. The plan entailed Yamato beaching itself at Okinawa to serve as a stationary artillery platform for the Japanese.

The United States Navy was able to anticipate the Japanese mission because of the interception and decryption of their radio communications. Opting for an aerial assault rather than deploying battleships, the American forces launched 300 aircraft from Admiral Mitscher’s carrier fleet on 7 April 1945. This operation successfully sank the Yamato, the largest battleship in the world, using bombs and torpedoes.

This event underscored the superiority of aircraft over battleships in naval warfare. The destruction of the Yamato signified the decline of the battleship era and the ascendance of aircraft carriers as the predominant maritime force.

Conclusion

Naval warfare in the Pacific had significantly evolved over time. While World War I featured minor naval engagements, World War II was characterised by extensive naval campaigns and battles. During this period, aircraft carriers had emerged as the dominant force. Engagements in regions such as Melanesia, Micronesia and the Philippines illustrate this transformation. The battles for Guadalcanal, the strategic bypassing of Truk Lagoon, the costly lessons of Tarawa, and the sinking of the Yamato demonstrated that naval supremacy was now determined by air power rather than battleship artillery fire. The Battle of Leyte Gulf was a pivotal victory facilitated by the combined efforts of aircraft carriers, submarines, and amphibious forces.

The naval engagements of the Pacific War imparted critical lessons that remain relevant today. The “island hopping” strategy, which concentrated on key enemy positions, significantly influenced U.S. military policy post-war, particularly during the Cold War. The logistical challenges encountered in campaigns across the Pacific, such as those in the Aleutian Islands and Guadalcanal, provided valuable insights into the management of supplies and forces. The evolution of amphibious warfare, from the demanding landings at Tarawa to more refined operations, enhanced the U.S. Marine Corps’ proficiency in expeditionary operations. The political objective of liberating the Philippines and the strategic imperative to secure the Ryukyu Islands illustrated the interconnectedness of political and military objectives, culminating in a victory in the Pacific War.

“…We are the sea, we are the ocean, we must wake up to this ancient truth and together use it to overturn all hegemonic views that ultimately aim to confine us again….” Epeli Hau’ofa