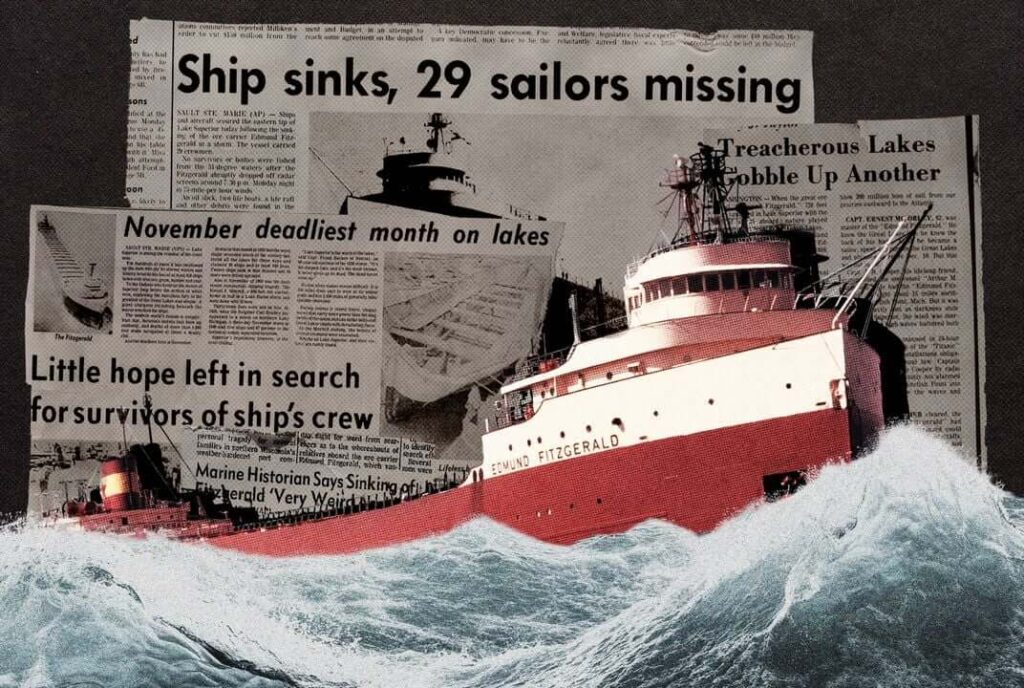

Fifty years ago, on November 10, 1975, the SS Edmund Fitzgerald, carrying 29 sailors, suddenly vanished without warning about 17 miles north–northwest of Whitefish Point, Michigan. There were no distress calls, no survivors, and virtually no floating debris. Just a brief radar blip—and then silence. When the Fitzgerald’s signal disappeared from the screens of the Arthur M. Anderson, a sister ship sailing close behind, Captain Bernie Cooper instinctively understood what it meant: the largest ship on the Great Lakes was gone.

Even today, half a century later, the sinking of the SS Edmund Fitzgerald remains one of the most mysterious and unforgettable maritime tragedies in North American history. The wreck was eventually found broken cleanly into two massive sections on the floor of Lake Superior, a discovery that launched decades of scientific investigation and heated debates over how such a giant vessel could vanish without a single call for help. The suddenness of the loss, the absence of witnesses, and Lake Superior’s refusal to reveal its secrets, all combine to ensure that the Fitzgerald’s story continues to haunt American folklore.

The legend of the Edmund Fitzgerald remains the most mysterious and controversial of all shipwreck stories—second only to the Titanic in the reach of its cultural imprint. Much of this lasting fame is owed to Canadian folk singer Gordon Lightfoot, whose 1976 ballad, “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald,” transformed the tragedy from a prominent news story into a piece of enduring cultural mythology. Yet beneath the poetry lies a serious question: how could a modern, state-of-the-art freighter break apart so suddenly and completely?

Even fifty years later, the most perplexing question lingers: How could a 222-metre, 26,000-tonne ship sink without a trace? Why does this tragedy occupy such a powerful place in public memory? And what have we truly learned since that terrible night?

SS Edmund Fitzgerald’s Final Voyage

By 1975, the SS Edmund Fitzgerald was an icon of maritime pride and engineering ambition. One of the largest and fastest ships to ever sail the Great Lakes, it was admired for its speed and sleek performance—so much so that sailors joked that when the Fitzgerald passed you, all you could do was wave at her disappearing stern.

The ship began its final, ill-fated journey on November 9, 1975, fully loaded with 26,116 long tons of taconite pellets from Superior, Wisconsin. Its destination was a steel mill on Zug Island near Detroit. Following several miles behind was the smaller but sturdy SS Arthur M. Anderson, commanded by Captain Bernie Cooper.

The voyage began smoothly. But by the evening of November 9, both captains—aware of a rapidly intensifying storm—decided to take a more northerly route across Lake Superior to seek shelter along the higher Canadian shoreline before turning southeast toward Whitefish Point.

Through the night and into the next day, the weather deteriorated dramatically. Winds strengthened into a violent storm, with gusts reported well above hurricane force. Waves rose to 20–25 feet, with occasional monstrous seas towering even higher. Thick snow squalls swept across the lake, reducing visibility to a few ship lengths. The Fitzgerald soon reported multiple problems: a list to starboard, water coming aboard, and a total loss of both its radar units. The Anderson’s captain later recalled his own ship being struck by massive seas that smashed over the wheelhouse—an ominous sign of what the lower-riding Fitzgerald must have been enduring.

By early evening on November 10, both vessels were desperately fighting their way toward Whitefish Bay, the Fitzgerald still leading and the Anderson struggling to keep her on radar. Navigational aids around Whitefish Point had been knocked out by the storm, leaving the captains to rely on dead reckoning, intermittent radar glimpses, and sparse radio checks.

The Fitzgerald’s wreck was located on November 14, just four days after its disappearance. A U.S. Navy P-3 Orion aircraft using advanced sonar and magnetic detection equipment identified the remains in 530 feet of frigid Lake Superior water. The ship lay in two enormous pieces, resting roughly 17 miles northwest of Whitefish Point. That discovery marked the beginning of decades of exploration, speculation, and controversy.

SS Arthur M. Anderson’s Role

The Arthur M. Anderson played a unique and sombre dual role as a steadfast companion during the storm and primary witness to the tragedy.

As both ships battled winds up to 90 miles per hour and waves approaching 35 feet, the Anderson maintained radio contact with the Fitzgerald. At one point, Captain Cooper observed the Fitzgerald passing dangerously close to the shallow waters around Six Fathom Shoal near Caribou Island.

By late afternoon on November 10, the Fitzgerald’s situation had deteriorated. At 3:30 p.m., Captain McSorley reported serious structural damage—including the loss of a fence rail and compromised vents, a critical issue because if the cargo hold vents were no longer watertight, water could flood the taconite pellets and destroy the ship’s stability. He also reported a heavy list and the continuous use of two bilge pumps to fight the increasing water. Without radar, McSorley was relying almost entirely on the Anderson to guide him to Whitefish Bay.

But shortly after 7:15 p.m., the Fitzgerald’s radar blip vanished.

Captain Cooper immediately contacted the Coast Guard and, despite the punishing storm, turned his ship around to lead the first search mission. It was the Anderson’s crew who found the Fitzgerald’s lifeboats—empty and battered by the storm.

Their testimony became central to every investigation and remains the last living connection to the ship’s final hours.

The Last Transmission

As the storm reached its peak, the Anderson briefly lost the Fitzgerald on radar around 7:10 p.m. Captain Cooper radioed Captain McSorley and asked, “How are you doing?”

McSorley replied, “We are holding our own.” It was his final transmission.

Ten minutes later, the Fitzgerald was gone.

When the storm subsided, the Coast Guard searched the lake but found nothing that could explain how a ship of that size vanished so completely.

What We Learned — And What We Did Not

If there is one lesson the Fitzgerald teaches, it is that no ship is unsinkable—not in 1975, and not today. The Titanic taught it once. The Fitzgerald taught it again. Every generation must relearn this truth.

The tragedy spurred sweeping reforms across Great Lakes shipping. Within a year:

- Mandatory survival suits were adopted.

- Ships were required to carry depth finders and upgraded radar.

- Weather forecasting and advisories became more precise.

- Loading procedures for bulk carriers were revised.

- Structural inspections became more rigorous.

These reforms made Great Lakes shipping significantly safer. Yet data shows that climate change is making storms on the Great Lakes more frequent and more violent. Lake Superior is warming faster than nearly any other large lake in the world.

Nature did not become safer. We became more prepared.

Modern vessels now use digital radar, satellite weather, GPS, AIS tracking, and stronger hulls. Yet ships continue to sink around the world. Technology narrows risk, but it never eliminates it.

In that sense, the Edmund Fitzgerald is more than a shipwreck—it is a reminder of our enduring vulnerability.

Edmund Fitzgerald @ 50: What the Anniversary Means Today

Anniversaries are not just about the past; they are about what we choose to remember. On the 50th anniversary of the Fitzgerald’s sinking, three reflections stand out.

- Remember the People, Not Just the Ship

It is easy to romanticize the massive vessel, the haunting final radio call, and the dramatic silhouette. But the heart of the story is the 29 men who never returned—working sailors, husbands, fathers, and sons. Their loss is the true tragedy.

2. Respect the Power of Inland Seas

The Great Lakes behave not like lakes but like oceans. Their storms rival the North Atlantic. They demand humility, respect, and constant preparedness.

3. Preserve the Story as a Warning, Not Just a Legend

Legend gives the Fitzgerald emotional power—but mythmaking can blur reality. The story must remain:

- a reminder that even mighty ships can fall

- a caution about the force of nature

- a testament to the need for relentless safety

- a warning that ordinary voyages can become catastrophes

To treat the Fitzgerald only as folklore is to forget the lessons paid for in lives.

Why This Shipwreck Became the Stuff of Legend

North America has witnessed far deadlier maritime tragedies. More than 800 people died when the Marquette & Bessemer No. 2 disappeared. Over 800 died in the Eastland disaster in 1915. Yet it is the Edmund Fitzgerald—with 29 lost sailors—that persists so vividly in public memory.

Every November 10, their names are read aloud at memorial ceremonies across the Great Lakes. At the Mariners’ Church of Detroit, the bell tolls 29 times—one for each life lost.

The loss endures not merely as folklore, but as family history, maritime history, and a powerful reminder of the lake’s eternal might.

Conclusion:

Fifty years after the Edmund Fitzgerald disappeared beneath the waves of Lake Superior, its story still feels unfinished. The investigations have produced data, theories, and reforms—but no final, uncontested answer. What remains beyond doubt is the courage of the men who sailed her, the raw power of the lake that claimed them, and the enduring responsibility of all who work at sea to learn from such losses. As the bell tolls 29 times each November, the Fitzgerald reminds us that progress at sea is always written in the names of those who never came home.