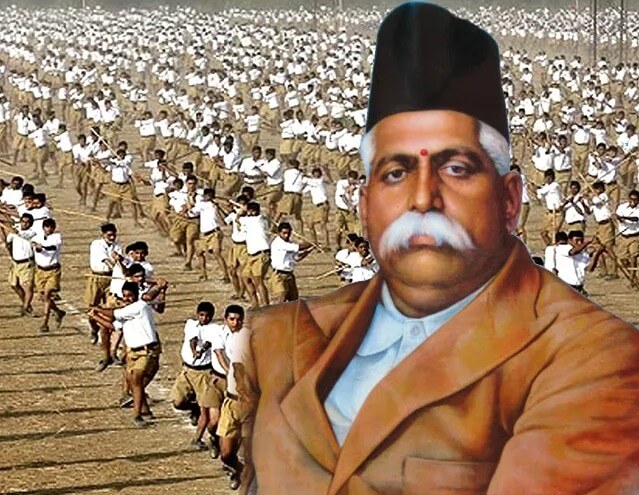

When Dr. Keshav Baliram Hedgewar founded the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) in Nagpur on Vijaya Dashami in 1925, his mission was neither to form a political outfit nor incite religious militancy. Rather, Hedgewar sought to revive the self-confidence of a colonized Hindu society and rebuild a national consciousness eroded by centuries of external rule. One hundred years later, as the RSS marks its centenary in 2025, the organization has become arguably the most consequential socio-political movement in independent India, with deep roots in culture, education, service, and governance.

Its centenary is not just a moment for commemoration but also for reflection—how an organization with modest beginnings mushroomed into a civilizational force shaping India’s political landscape, social ethos, and national identity.

From Hedgewar’s Vision to a National Movement

The RSS began quietly, almost humbly, as a voluntary cadre for moral and physical training of young men. Dr Hedgewar believed that national regeneration required disciplined individuals imbued with devotion to Bharat Mata and committed to selfless service. In the 1920s, this was a radical idea. The freedom movement was still dominated by Congress-led constitutional politics and Gandhian non-violence. Hedgewar’s focus on inner reform, character-building, and daily shakhas offered an alternate form of awakening—less political, more foundational.

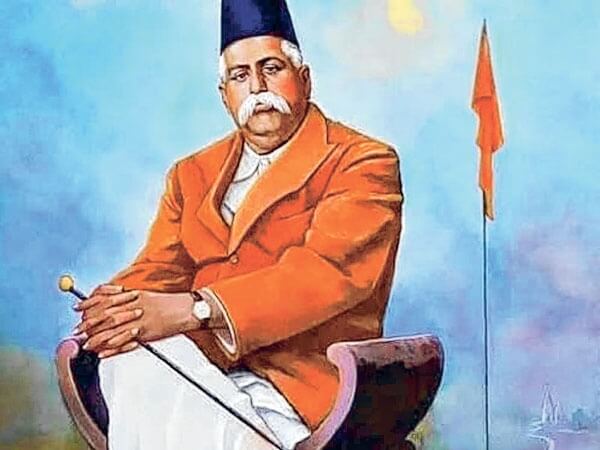

His successor, M.S. Golwalkar, or Guruji, who became Sarsanghchalak in 1940, gave the RSS a philosophical coherence. Golwalkar’s writings, especially “We, or Our Nationhood Defined” and “Bunch of Thoughts,” laid down the ideological bedrock of what came to be called “Hindutva.” Under him, the RSS perfected its decentralized organizational structure, expanding through prant (state) and shakha (local) levels. It developed an astonishing ability to replicate its discipline and messaging across geographies without centralized command or financial dependence—a strength that continues to sustain it today.

Adaptation and Expansion in Post-Independence India

The first decades after 1947 tested the RSS’s resilience. After Mahatma Gandhi’s assassination in 1948, the organization was banned and faced severe public hostility. But instead of collapsing, the RSS grew stronger, partly because it adapted. It began to project itself as a cultural rather than political organization, focusing on social service and moral education. This phase also saw the emergence of the Jan Sangh, the Bharatiya Mazdoor Sangh, and Vidya Bharati schools—each a specialized arm extending RSS influence across diverse domains.

During the 1960s and 70s, the RSS combined discipline with quiet grassroots work. It avoided confrontation even when banned during Indira Gandhi’s Emergency (1975–77), and its volunteers became symbols of resistance to authoritarianism. The post-Emergency years marked a turning point: nationalist ideas, long marginalized as communal, gained moral legitimacy. The RSS, by then, had spread nationwide, with millions of swayamsevaks engaged in education, relief work, and rural development through its various affiliates.

The Political Apex: From Jan Sangh to BJP

No analysis of the RSS’s century can ignore its political expression through parties it inspired. The Bharatiya Jana Sangh, established in 1951 under Syama Prasad Mookerjee, was the first organized politico-ideological extension of the Sangh’s worldview. It sought to translate cultural nationalism into governance. Through leaders like Deendayal Upadhyaya, the Jana Sangh articulated the doctrine of Integral Humanism—an alternative to Western capitalism and communism emphasizing dharmic ethics in economics and polity.

Integral Humanism became the guiding principle of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), founded in 1980, which grew into the world’s largest political party under leaders who began their journeys as swayamsevaks. The political rise of the BJP and the RSS’s ideological mainstreaming reached a decisive moment in 2014, with Narendra Modi—himself a lifelong pracharak—leading the BJP to power with an absolute majority. It marked the culmination of a century-long ideological journey: from fringe to the core of India’s governance, from a shakha in Nagpur to the Prime Minister’s Office in New Delhi.

A Cultural Powerhouse Beyond Politics

Yet, it would be a mistake to view the RSS merely through its political offspring. Its deeper contribution lies in the socio-cultural sphere—the quiet re-engineering of national consciousness. Through its affiliate organizations, the Sangh has built one of the world’s most extensive voluntary networks. Vidya Bharati runs more than 13,000 schools imparting value-based education. The Vanvasi Kalyan Ashram works among tribal communities to foster social integration. Seva Bharati’s humanitarian work, from disaster relief to health care, cuts across religion and caste.

RSS volunteers have been on the ground during every major national crisis—the 2001 Gujarat earthquake, the 2004 tsunami, the COVID-19 pandemic—carrying symbolic saffron flags but practical medicine, food, and manpower. Its influence also extends into ideological and intellectual domains through think tanks like the Bharatiya Vichar Sadhana and cultural arms like Samskrit Bharati, which promote Sanskrit and Indic scholarship.

Crucially, the RSS has reshaped the vocabulary of nationalism. The phrase “Bharat Mata ki Jai” or the emphasis on “cultural unity” found resonance across the spectrum. Even critics now concede that Indian politics is conducted in the language that the Sangh long propagated—nation-first, development with pride in heritage, and cultural self-assertion.

The Evolution of Thought: From Uniformity to Inclusivity

Over its 100 years, the RSS’s ideology too has evolved. Hedgewar’s call for Hindu unity once emphasized cultural consolidation in a fragmented society. But in a globalized, multi-faith India, the organization has gradually broadened its rhetoric. Its leadership today stresses “Samajik Samrasta” (social harmony) and “Sabka Saath, Sabka Vikas”—phrases that consciously attempt to bridge caste and community divides. The RSS’s outreach to Dalits, tribals, and even minority groups reflects this ideological maturing and adaptation to Indian democracy’s inclusive expectations.

Recent Sarsanghchalaks, including Mohan Bhagwat, have acknowledged the need for dialogue and modern reinterpretation of core principles. Bhagwat’s repeated emphasis on “Hindutva as inclusive,” his interactions with Muslim intellectuals, and statements about “the DNA of all Indians being one” show an organization attempting to merge conviction with accommodation. The modern Sangh appears less militant and more mindful of its civilizational responsibility as the keeper of India’s cultural compass.

Criticism and Controversy

Yet the RSS’s century-long journey is not without controversy. Opponents, especially from left-leaning and secular circles, accuse it of promoting majoritarian nationalism and eroding India’s pluralism. They point to its early admiration of European ethnonational movements and its alleged intolerance toward minorities. The demolition of the Babri Masjid in 1992 by kar sevaks linked to the broader Sangh Parivar continues to cast a shadow in secular discourse. The organization’s critics view this as evidence that its cultural nationalism often borders on religious exclusivism.

The RSS counters this with facts on its service record and the constitutional loyalty of its cadres. It argues that pluralism must be rooted in cultural confidence, not denial of identity. Its leaders clarify that “Hindutva” is a civilizational ethos, not a religious dogma—a worldview accepting diversity within unity. While detractors dismiss this as rhetoric, the Sangh’s continuing expansion into previously non-Hindu communities offers partial vindication. Its historic opposition to sectarian conversions and emphasis on “homecoming” (ghar wapsi) reflect cultural preservation rather than aggression, at least from its own perspective.

The balancing act between cultural assertion and democratic pluralism remains the RSS’s greatest modern challenge. As India urbanizes and digitizes, the shakha-based pedagogy of discipline and daily volunteering faces the test of relevance in a social media era. The RSS leadership is aware of this, and has been quietly modernizing its outreach—embracing digital portals, youth dialogues, and even CSR collaborations without compromising core values.

An Institution of Continuity in a Changing India

In a nation where most institutions—political parties, trade unions, even civil society groups—fracture within decades, the RSS’s hundred-year survival is in itself remarkable. Its core strength lies in three principles: ideological clarity, voluntary discipline, and adaptability. It survives not by rigid control but by organic decentralization. Each karyakarta feels ownership of the mission; each generation reinvents the method without altering the essence.

The centenary also reaffirms a paradox: the Sangh is both conservative and revolutionary. Conservative in its reverence for tradition, family, and faith; revolutionary in its defiance of imported ideologies and its emphasis on self-reliance and social equality. The RSS’s project is not merely political transformation but a cultural renaissance—an attempt to recast India’s modernity in its own image, free from colonial and Western categories.

This explains why its ideas have outlasted regimes, bans, and opposition. The concept of “Rashtra Dharma”—duty toward the nation—is now deeply embedded in India’s mainstream consciousness. Whether one agrees with its interpretations or not, the RSS has ensured that India’s national debate increasingly revolves around its own civilizational vocabulary rather than borrowed isms.

Looking Ahead: The Next 100 Years

As it enters its second century, the RSS faces new responsibilities and tests. The younger India of 2040 will be globally connected, technologically driven, and less patient with traditional hierarchies. The challenge for the Sangh will be to retain moral authority among this demographic while adapting its organizational culture. The concept of daily shakhas might evolve into digital learning forums; seva projects may align with sustainability and technology; its nationalism must converse with a globalized citizenry.

Moreover, the RSS’s moral legitimacy depends on how it handles power. The close alignment of the Sangh with the ruling BJP invites both influence and scrutiny. Maintaining an independent moral compass, not merely a political one, will determine whether the RSS remains a cultural conscience or becomes a partisan organ. Hedgewar’s vision was never about power; it was about character. As the centenary commemorations echo his words, the organization must keep the focus on “nation before self” rather than “party before nation.”

Conclusion: A Century That Changed India

One hundred years after its founding, the RSS stands as a testament to the power of continuity, conviction, and grassroots discipline. From a handful of volunteers in Nagpur to lakhs of swayamsevaks worldwide, its transformation mirrors India’s own journey—from colonization to confidence, from fragmentation to self-definition. It has inspired admiration, criticism, imitation, and fear—but never indifference.

As India steps into its centenary decade of independence and the RSS into its own century, both face similar questions of identity, global relevance, and internal unity. The RSS’s legacy lies not merely in the government it influences but in the consciousness it has shaped—an unbroken cultural thread reminding a billion people that the strength of a civilization rests not in its slogans, but in the character of its citizens.

In that sense, the RSS at 100 is not just a milestone—it is a mirror reflecting how India has come to understand itself.