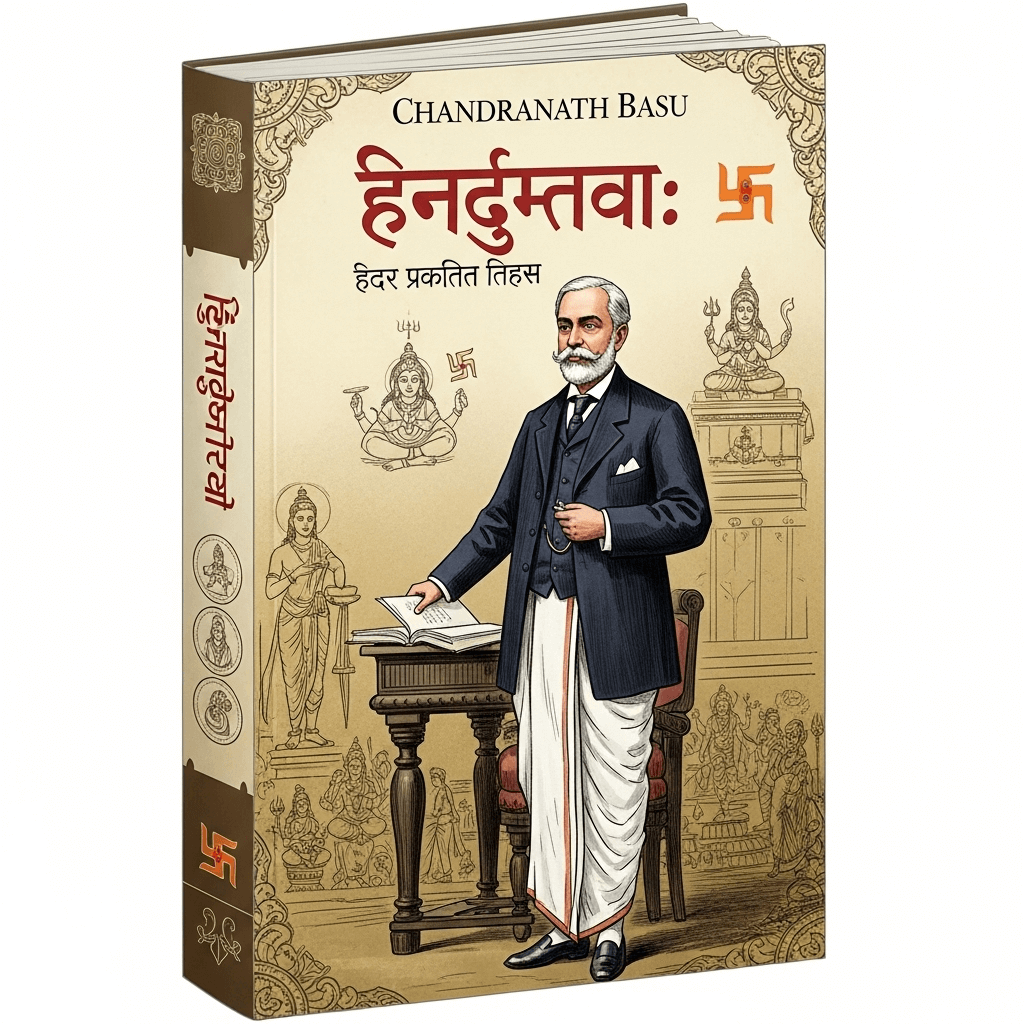

The term “Hinduism,” coined by British colonisers, fused Sanskrit and English morphemes to categorise the diverse, native spiritual practices of the Indian subcontinent, imposing a rigid, foreign framework that misrepresented their fluid, pluralistic nature. To reclaim an indigenous identity, Chandranath Basu coined “Hindutva” in 1892, in his eponymous book, presenting it as a modern Sanskrit term for Sanatana Dharma, the eternal religion that transcends geographical, cultural, and temporal boundaries. In Basu’s vision, Hindutva encapsulates the timeless essence of this ancient religion, rooted in universal principles. However, this spiritual term was misappropriated by Vinayak Damodar Savarkar in 1923, who used Hindutva it to name his politico-nationalistic ideology, a distortion we explicitly reject. This article elucidates Hindutva as a synonym for Sanatana Dharma, exploring philosophical underpinnings, historical manifestations, and global influence to present it as a universal spiritual framework addressing existential questions about divinity, human purpose, and ethical living.

Origin of the term Hindu:

The term “Hindu” is deeply rooted in the ancient cultural and historical identity of the Indian subcontinent, derived from the Sanskrit word “Sindhu.” In the Mahabharata, Jayadratha, king of Sindhu and husband of Dushala, sister of the Kauravas, is consistently called “Saindhava” (of Sindhu), highlighting that “Sindhu” referred not only to the river but also to the region and its people, as seen today in Pakistan’s Sindh province and its Sindhi inhabitants. Hindu texts and traditions place the onset of the Kali Yuga in 3102 BCE, immediately after the Kurukshetra War depicted in the epic Mahabharata, suggesting that even long before 5,100 years ago, northwestern Indians identified as “Sindhus,” a name echoed across time.

Linguistic evolution further shaped the term. In northwestern Indian Prakrits and neighbouring Persian, the sibilant “s” often transformed into an “h,” rendering “Sindhu” as “Hindu” in Persian usage. The Greeks adapted it to “Indos,” softening the accent, while much of Europe and later America adopted “India” and “Indian.” In the 7th century CE, the Chinese traveller Xuanzang, during his extensive journeys through India, referred to the people as “Shintus” or “Hintus,” reinforcing the term’s ancient roots. By adding the Sanskrit suffix “-sthan” (place or land), “Sindhusthan” or “Hindustan” emerged as a name for the entire subcontinent, mirrored in regional names like Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Kazakhstan.

The term “Haindavam,” meaning “of Hindu,” adapted to the Telugu linguistic framework, underscores that “Hindu” was not only prevalent in northern India but also deeply rooted in Dakshinapatha (South India) long before modern times. In Telugu, “Haindavam” is often used to denote the Hindu religion or Sanatana Dharma, reflecting its profound historical and cultural resonance. In learned and literary circles, Haindavam is frequently mentioned alongside other philosophical and religious traditions, such as Advaitam, Dvaitam, Shaktam, Shaivam, Vaishnavam, Jainam, and Bauddham, highlighting its longstanding usage across diverse intellectual contexts.

Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, a prominent Indian scholar, explains that “Hindu,” as a Prakrit derivative of a Sanskrit term, would not typically appear in Sanskrit literature. Nevertheless, its significance is acknowledged by esteemed lexicographers like Vaman Shivram Apte of Maharashtra and Taranath Tarkavachaspati of Bengal, who included it in their works, underscoring its cultural importance. Savarkar firmly rejects claims that “Hindu” or “Hindustan” originated from Persian or Arabic sources, asserting that these terms were mere phonetic adaptations by Persians, as well as by the northwestern Indian Prakrits, of Sanskrit terms.

Historical evidence supports this view. In the 8th century, Bappa Rawal, founder of the Guhila Rajput dynasty, was hailed as “Hindu Suraj” (Hindu Sun) for repelling Arab invasions, with Rawalpindi named in his honour. In Dakshinapatha, the kings of the Vijayanagara Empire (1336–1646) adopted the title “Hindu Raya Suratrana” (or simply “Hindu Suratrana”), combining the Sanskrit words “sura” (god) and “trana” (protector), signifying their role as guardians of Hindu deities and religion.

The notion that “Hindu” was an external imposition by Persians or others is baseless. Naming conventions across cultures—such as Hindi speakers referring to Russia as “Roos” or China as “Cheen”—effectively illustrate how foreign pronunciations adapt native terms without inventing them. Persians called the people of India “Hindus” because that was their identity, rooted in an ancient civilisation. “Hindu” is an intrinsic marker of an ancient Indian identity rooted in the Sanskrit term “Sindhu,” rejecting claims of external imposition by Persians or others. To claim otherwise distorts history. The term “Hindu” stands as a testament to a civilisation that has thrived for millennia.

Why the Western Label ‘Hinduism’ and Related Terms Must Be Rejected

Naming carries the power to define and control. Proper names of people or religions are typically retained across languages, preserving their cultural integrity. Yet, British colonial scholars, in a mischievous and agenda-driven act, renamed the religions originating in India—Sanatana Dharma, Buddha Dharma, Jaina Dharma, and Gurmat—as “Hinduism,” “Buddhism,” “Jainism,” and “Sikhism,” imposing a Eurocentric lens that eroded their agency. Muslims successfully rejected the colonial misnomer “Mohammedanism,” reclaiming their faith’s true name, Islam. In contrast, Hindus, including Bauddhas, Jainas, and Sikhs, continue to bear the burden of imposed labels like “Hinduism,” “Buddhism,” “Jainism,” and “Sikhism,” yet to fully restore their indigenous identities.

Further, “-ism” typically denotes ideologies, not religions, yet the British used it to recast these fluid, non-dogmatic religions as rigid systems akin to Marxism, obscuring their pluralistic ethos. In contrast, colonial scholars, predominantly Christians, reserved “-ity” for “Christianity” to signify a dynamic collective identity, marginalising Indian traditions as static and exotic. The indigenous Sanskrit suffix “-tva,” as in Hindutva, aligns with “-ity” by expressing a state of being but was deemed incompatible with Western taxonomic categories by colonial scholars. This terminological disparity reveals a colonial agenda to essentialise and dominate these traditions. Focusing on Sanatana Dharma, this article rejects “Hinduism” to reclaim its indigenous identity as Hindutva.

The Historical and Terminological Origins of Hindutva

The term “Hindutva” was introduced by Chandranath Basu in his 1892 book Hindutva, where it served as a modern Sanskrit term for Sanatana Dharma, meaning “eternal religion.” Basu’s coinage was a response to the colonial term “Hinduism,” which emerged in the 19th century as British scholars and administrators sought to categorise the diverse religious practices of the Indian subcontinent. The suffix “-ism” implied a rigid doctrinal system, which many practitioners felt misrepresented the fluid and pluralistic nature of their traditions. Basu’s Hindutva sought to restore an indigenous identity, emphasising the eternal and universal essence of the tradition.

However, the term was later appropriated by Vinayak Damodar Savarkar in his 1923 eponymous book, where it was reframed as a politico-nationalistic ideology. This reinterpretation diverged significantly from Basu’s vision, which was religious rather than political. We thus reject Savarkar’s political appropriation of Hindutva. By situating Hindutva as synonymous with Sanatana Dharma, we align with Basu’s intent to describe a spiritual tradition unbound by geography or politics.

The historical context of the origin of the term Hindutva in 19th century, reveals a tension between indigenous self-definition and colonial categorisation. Sanatana Dharma, as a term, reflects the tradition’s emphasis on eternal truths that transcend time and place. The Vedas, Upanishads, and other foundational texts emphasise universal principles, such as the oneness of existence and the pursuit of liberation, rather than localised dogmas. This universality forms the basis for understanding Hindutva as a spiritual tradition, a theme explored further in subsequent sections.

Philosophical Foundations of Hindutva: The Nature of Divinity

At the heart of Hindutva lies a sophisticated metaphysical framework that addresses the nature of divinity and existence. The Rigveda (1.164.46) declares, “ekam sat vipraa bhudhaa vadanti” — the truth is one, though the wise call it by many names. This aphorism encapsulates the tradition’s monistic yet pluralistic understanding of divinity, centered on the concept of Brahman.

Nirguna and Saguna Brahman

Brahman, the ultimate reality, is conceptualised in two forms: Nirguna Brahman and Saguna Brahman. Nirguna Brahman is attributeless, infinite, and beyond human comprehension — a formless, timeless essence that transcends space and causality. This abstract concept challenges human understanding, as it exists beyond sensory and intellectual perception. Saguna Brahman, in contrast, is Brahman with attributes, personified as Ishvara, the personal God who is omnipotent (sarvasaktivat), omnipresent (sarvavyāpin), and omniscient (sarvagnya). The Isavasya Upanishad’s aphorism “Īsāvāsyamidam sarvam” — divinity pervades everything — underscores the immanence of Ishvara in the universe.

The distinction between Nirguna and Saguna Brahman is not a dichotomy but a continuum, reflecting the limitations of human perception. Ishvara manifests in various forms, such as Brahma (creation), Vishnu (preservation), and Shiva (dissolution), as well as deities like Sarasvati (knowledge) and Lakshmi (wealth). These deities are not separate gods but facets of Ishvara’s infinite roles, a concept that distinguishes Hindutva’s polytheism from the fragmented polytheisms of other traditions. The use of gender-neutral or flexible pronouns for Brahman — He, She, or It — further emphasises its transcendence of human categories.

Avatāra and Divine Compassion

Hindutva teaches that when righteousness (dharma) declines and irreligion rises, Ishvara incarnates as an avatāra to restore balance. Figures, such as Rama and Krishna, celebrated in texts like the Ramayana and Mahabharata, are considered divine incarnations who guide humanity through example and teaching. This doctrine of avatāra reflects Hindutva’s dynamic engagement with the world, emphasising divine compassion and the active role of divinity in human affairs.

The philosophical interplay between Nirguna and Saguna Brahman, coupled with the concept of avatāra, provides a framework for understanding the relationship between the infinite and the finite, the eternal and the temporal. This duality allows Hindutva to accommodate diverse spiritual practices within its framework, from abstract meditation on Nirguna Brahman to devotional worship of Saguna deities, making it a inclusive tradition.

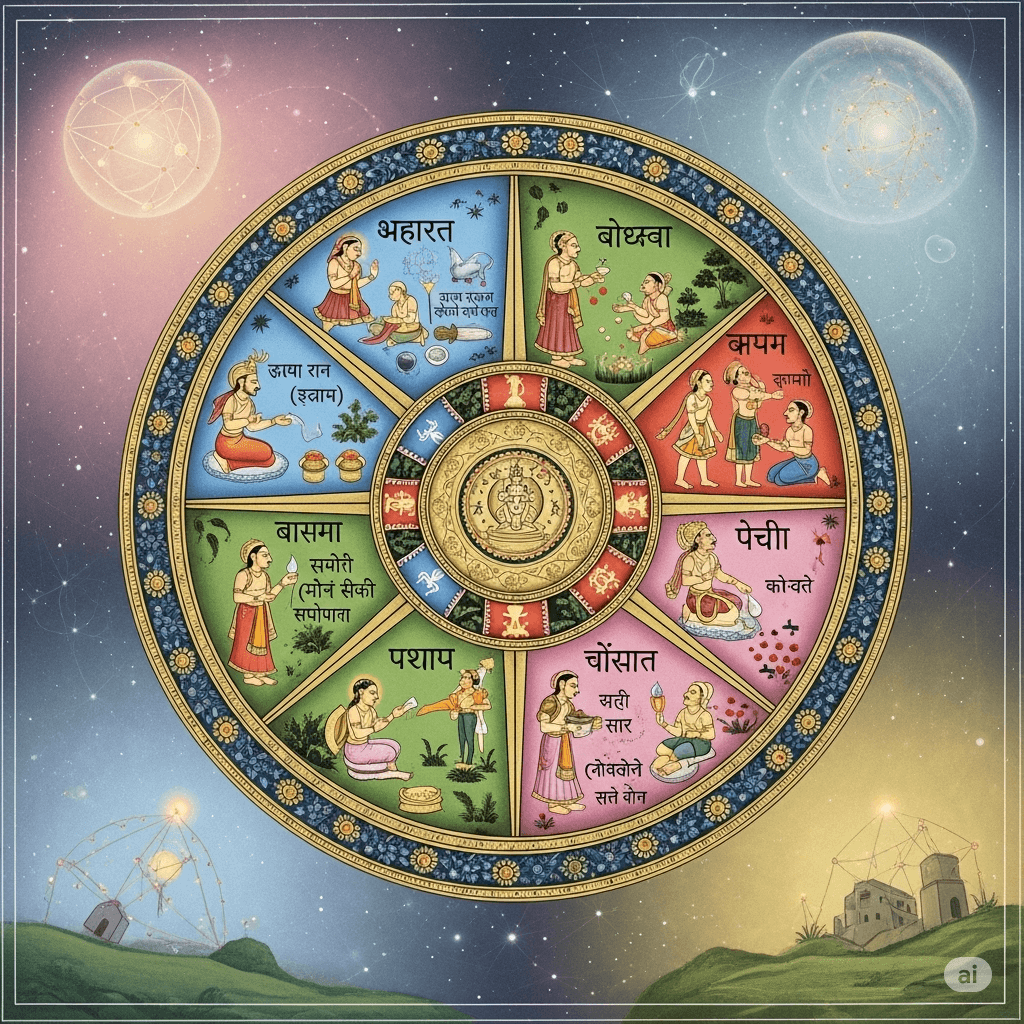

Core Doctrines: Karma, Punarjanma, Rta, and Purushārtha

Hindutva’s philosophical system is anchored in four interrelated doctrines: karma, punarjanma, rta, and Purushārtha. These concepts provide a comprehensive framework for understanding human existence, ethical responsibility, and spiritual liberation.

Karma: The Law of Cause and Effect

Karma, the principle of cause and effect, governs the moral consequences of actions. It is categorised into three types:

- Sanchita Karma: The accumulated sum of actions from past lives, awaiting fruition.

- Prarabdha Karma: The portion of Sanchita Karma active in this life, shaping your present. It cannot be changed and must be lived through.

- Aagami Karma: Actions performed in the present which will add to Sanchita Karma and influence future outcomes.

The results of karma, called karmaphala, bring joy from good deeds and pain from bad ones. Īshvara does not cause this pleasure or suffering; He is the karmaphaladāta —the impartial dispenser of consequences of your own karma. Karma teaches that our present choices shape our future. Understanding this discourages harmful actions, which lead to suffering, and encourages good deeds, which bring happiness. Each person, therefore, crafts his own reality through his actions. The essence of doctrine of karma is that man is maker of his own destiny.

Punarjanma: The Cycle of Rebirth

Punarjanma, or rebirth, holds that life and death is a cycle. Life neither begins with one birth nor ends with one death. Each birth ties us to the consequences, karmaphala, of our past actions. A person may not always be reborn as a human; depending on his karma, he could return as a lower being — this is called jatyantara-punarjanma. Through performing prescribed rituals, spiritual practice, good deeds, and true wisdom, one can earn enough positive karmaphala to achieve moksha or janmarahityam— a state of eternal bliss and liberation from the cycle of birth and death.

Rta: The Cosmic Order

Rta is the cosmic rhythm that sustains existence, governing natural and moral laws. It imposes five debts (pancha riña) on individuals from birth:

- Pitru Riña: Debt to ancestors, fulfilled through familial duties.

- Deva Riña: Debt to deities, repaid through worship and rituals.

- Rishi Riña: Debt to sages and teachers, honoured through learning and teaching.

- Nara Riña: Debt to humanity, met through service and compassion.

- Bhūta Riña: Debt to nature, addressed through environmental stewardship, expressed in practices like venerating rivers, trees, and mountains as divine manifestations.

The concept of riña fosters a sense of interconnectedness, reminding us of our gratitude to ancestors, deities, sages, and responsibilities to fellow humans, and nature. It curbs greed and urges us to contribute to humanity, religion, culture, and the environment. Nature worship, such as offering water to the sun or revering rivers like the Ganga, and ancestor worship, through rituals like Pitru Puja, integrate Hindutva’s cosmic and familial responsibilities, reinforcing rta’s role in universal harmony. Crucially, it affirms our place in a continuum of past and future, part of nature, not its owners or rulers.

Purushārtha: The Four Goals of Life

Purushārtha outlines four aims of human life, prioritised in ascending order:

- Artha: Material wealth and security, necessary for a stable life.

- Kāma: Pleasure and desire, fulfilling human emotional and procreational needs.

- Dharma: Righteousness and duty, aligning actions with moral and spiritual principles.

- Moksha: Liberation from samsara, the ultimate spiritual goal.

The concept of Purushārtha advocates a balanced, harmonious and meaningful life, integrating material, emotional, ethical, and spiritual dimensions. By prioritising dharma and moksha over artha and kāma, Hindutva encourages a life of purpose and transcendence.

Hindutva’s universal pro-nature principles — such as the oneness of truth, the pursuit of liberation, and the interconnectedness of existence — offer a framework for addressing global challenges, including environmental degradation, social inequality, and spiritual disconnection. By promoting ethical living and environmental stewardship, Hindutva aligns with modern movements for sustainability and justice.

Defining Hindutva: A Living Tapestry of Diversity of Unity

Hindutva defies simplistic definition, as scholarly attempts often fail to capture its vastness. Yet, it can be vividly understood through the metaphor of the Great Banyan tree, an ancient marvel of the Indian subcontinent. Like the banyan, Hindutva weaves a vibrant network of “roots” and “branches”— a rich mosaic of sub-traditions, from Vedic chants and Upanishadic inquiry to regional devotional rites, nature worship, and ancestor veneration. Each strand radiates distinct spiritual and cultural expressions within a polycentric web, yet all converge under a single, timeless canopy, spanning millennia to form a unified tradition of diversity. This canopy is not merely a passive cover but the vital embodiment of a shared essence—the sap, fluids, and DNA of Hindutva—that flows through every branch, sustaining its life and unity.

Unlike a tree with a solitary trunk, the Hindu banyan has no single founder or fixed origin. It flourishes as an intricate lattice of interwoven trunks and branches, each sustaining the others in a dynamic interplay of continuity and renewal. Sub-traditions like bhakti’s fervent devotion, Vedanta’s metaphysical rigor, or Yoga’s disciplined practice blend fluidly yet retain their distinctiveness, adapting to new contexts as some branches fade and others emerge, ensuring Hindutva’s enduring vitality. Though outwardly diverse, these traditions are not disparate but radiant manifestations of a singular, eternal essence — a polyfocal symphony where every note, from Vedic hymns to regional rituals, resonates with the same divine lifeblood of Hindutva. This polyfocality — the capacity for multiple focal points to emanate from a shared core — defines Hindutva, where diverse expressions are interconnected reflections of a single, unifying truth.

Hindutva’s diversity can also be likened to a polyfocal ellipse in geometry, where multiple foci — more than the two of a traditional ellipse — define a single, harmonious curve. In this n-ellipse, each point on the curve maintains a constant sum of distances to all foci, just as Hindutva’s varied practices, from Vedic rituals to bhakti devotion to nature and ancestor worship, converge around its core principles of karma, punarjanma, rta, and Purushārtha. This polyfocality ensures that, despite its manifold expressions, Hindutva remains a unified tradition, its diverse paths radiating from and sustained by a shared, eternal essence.

Alternatively, Hindutva mirrors an extended family, its members united by shared yet varied traits. Like kin bearing recognisable markers of lineage, its traditions — from Yoga’s discipline to rituals of nature worship — share features like reverence for the Vedas, the moral framework of karma, or the pursuit of moksha, embracing multiplicity without demanding uniformity. The sap of Hindutva — its core principles of the oneness of truth, karma, punarjanma, rta, and Purushārtha — flows through its diverse foundational texts (Vedas, Upanishads), philosophical systems (Vedanta, Yoga), devotional practices (bhakti), and traditions of ancestor and nature worship. This shared essence unifies Hindutva, ensuring that its outward diversity is not fragmentation but a vibrant reflection of its polyfocal unity.

Hindutva’s diversity-of-unity, distinct from unity in diversity, signifies that its core principles are the singular source from which diverse expressions flow, rather than disparate traditions unified retrospectively. These principles permeate every facet of Hindutva, forming the heart of its expansive phenomenon. Instead of attempting to rigidly define Hindutva (Sanatana Dharma), or who is a Hindu, this article outlines these core principles and traits shared across all Hindu sects, offering a lens to understand its vast, enduringly adaptive tradition, where the same life-giving essence sustains its boundless diversity.

Nature and Ancestor Worship in Hindutva

Hindutva embraces a profound reverence for nature and ancestors, weaving these practices into its spiritual and ethical fabric. These forms of worship are not peripheral but core expressions of the Hindutva, reflecting its holistic worldview that perceives divinity in the natural world and honours the continuity of lineage through ancestral veneration.

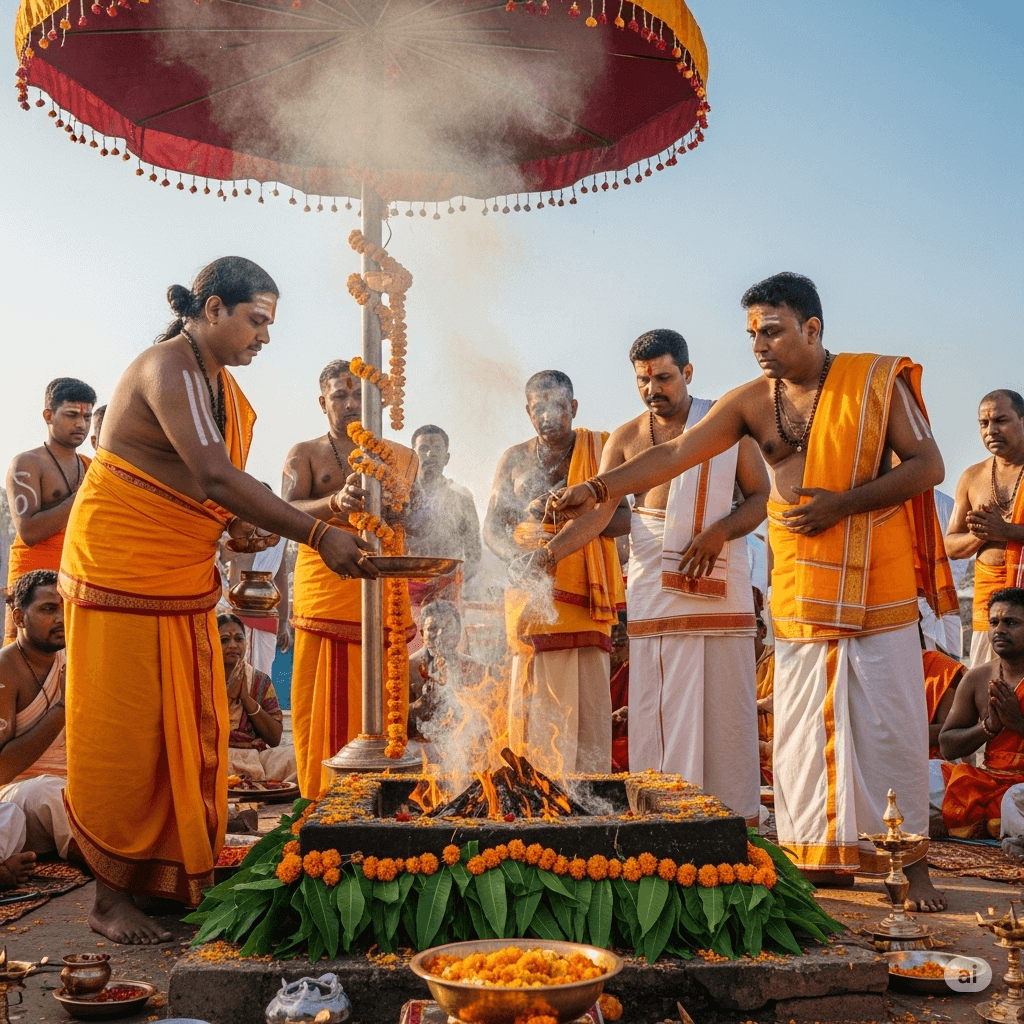

Nature Worship: The Divine in the Cosmos

Nature worship is deeply embedded in Hindutva, rooted in the Vedic recognition of the five elements (Pancha Mahabhutas) — earth, water, fire, air, and space — as manifestations of Brahman, the ultimate reality. Rivers, mountains like Kailash, and trees like the Peepal are venerated as sacred embodiments of divine energy. Deities such as Surya (sun), Agni (fire), Varuna (water), and Prithvi (earth) are celebrated in Vedic hymns and rituals, underscoring the belief that the cosmos is alive with divine presence. The concept of Bhūta Rina (debt to nature) mandates environmental stewardship, urging Hindus to protect and honour the natural world. This ecological consciousness, drawn from texts like the Rigveda and Bhagavad Gita, positions Hindutva as a tradition that resonates with modern environmental ethics, advocating harmony with the natural order as an expression of dharma.

Ancestor Worship: Honouring the Pitrus

Ancestor worship, known as Pitru Puja or Shraddha, is a key element of Hindutva, reflecting the tradition’s emphasis on familial and cosmic continuity. The concept of Pitru Rina, the debt to ancestors, acknowledges their role in sustaining lineage and spiritual heritage. During rituals like those performed in Pitru Paksha, offerings of pinda (rice balls), water (tarpana), and prayers are made to ensure the ancestors’ peace and blessings, believed to influence the living across cycles of birth and death (punarjanma). Ancestor worship reinforces the moral causality of karma, as it acknowledges the karmic legacy of ancestors and their ongoing connection to the living. This practice fosters a sense of gratitude and responsibility, grounding Hindutva’s ethical framework in familial and spiritual duty within the Purushārtha framework.

Integration with Hindutva’s Core Principles

Nature and ancestor worship are seamless extensions of Hindutva’s core doctrines — rta, karma, and Purushārtha. Nature worship aligns with rta by recognising the divine rhythm in the natural world, while ancestor worship upholds karma and punarjanma by honouring the karmic legacy of forebears. Both contribute to the pursuit of dharma and moksha, balancing material and spiritual aspirations within the Purushārtha framework. These practices, shared across Hindu sects, exemplify Hindutva’s diversity-of-unity, allowing varied expressions — from Vedic rituals to regional traditions — while remaining anchored in a shared metaphysical vision. By venerating nature and ancestors, Hindutva not only preserves its ancient heritage but also offers a timeless model for ethical living and ecological responsibility, relevant to global challenges.

Hindutva: A Universal Religion Beyond Geography

Hindutva, as a religion, transcends geography, rooted in the universal concept of the divine rather than a specific location. Like all major faiths, it venerates sacred sites—such as the Ganga, Mount Kailash, Kashi, or Tirupati — but their significance lies in their symbolic power, not their physical boundaries. The Ganga embodies vitality and purity, a universal ideal mirrored in rivers worldwide. Mount Kailash symbolises the spiritual ascent of every seeker, regardless of where they stand. These places inspire devotion, but Hindutva’s essence is not confined to them; it thrives wherever its principles are embraced.

The Vedas, foundational to Hindutva, celebrate universal forces—fire (Agni), wind (Vayu), and the boundless sky—unmoored from any single land. Originating in the Indian subcontinent along rivers like the Saraswati, Hindutva’s doctrines are eternal and unbound, adaptable to diverse cultures and nations. Its history reflects this expansiveness. The 12th-century Angkor Wat in Cambodia, adorned with Mahabharata carvings, stands as a testament to Vishnu’s universal reach. The late Kanchi Sankaracharya, His Holiness Chandrasekharendra Sarasvati Mahaswami, noted in Hindu Dharma (published by Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan) that even the distant Inca, Maya, and Aztec civilisations bear traces of Hindu influence, underscoring Hindutva’s far-reaching light. This observation by the Kanchi Mahaswami may invite skepticism, yet it reflects a Hindu historical consciousness unbound by linear time. As Julius Lipner notes, Hindu religious historical consciousness need not be subject to a linear understanding of time, as history in the Hindu tradition is not merely a chronology but a two-way assessment of the past in the light of present, and of the present in the light of past, where sacred history subsumes a teleological view. Within Hindutva’s framework, space is of a piece with time, the space-time continuum in which we live being an expression of prakriti, allowing cultural and spiritual resonances to transcend geographical and temporal boundaries, manifesting in diverse civilisations as expressions of eternal truths.

Hindutva remains a distinct and universal religion, not a political or nationalistic construct. Hindus worldwide—diverse in caste, region, language, or nationality—are united by a shared spiritual essence, perceived as one even by adversaries like Christianity and Islam, who label them pejoratively as “Heathen” or “Kafir,” respectively, despite these internal divisions. Though sacred sites like those in Pakistan, Bangladesh, or Tibet’s Mount Kailash hold significance, Hindutva’s endurance despite their territorial loss underscores that its essence lies beyond physical locations. Theologically and spiritually, Hindutva remains unshaken, proving its resilience and universality. Hindus living outside India, while revering India as a spiritual homeland, are equally Hindu, affirming that sacred sites are not the core of Hindutva. Practitioners globally can adopt its principles without forsaking their cultural or national identities, affirming Hindutva as a geographically boundless, roaming beacon of divine connection.

Limits of Inclusivity and Pluralism of Hindutva

While Hindutva embraces a pluralistic approach to divinity, which is singular in essence, and diverse spiritual practices, its inclusivity has defined boundaries. The diverse paths to divinity, as articulated by Lord Krishna in the Bhagavad Gita (e.g., 4.11: “In whatever way people approach Me, I receive them; all paths, Arjuna, lead to Me”), are firmly rooted in the framework of Hindutva. These paths—whether bhakti, jnāna, karma, or yoga—are expressions of its core principles, such as the oneness of truth and the moral order of karma. However, this pluralism does not extend to theologies that fundamentally oppose these principles, such as the prophetic monotheism of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, or to atheism and heterodoxies that are inherently anti-Hindu and reject Hindutva’s metaphysical foundations. These systems, with their exclusive claims to truth or denial of a divine order, stand in stark contrast to Hindutva’s principles of unified truth and the cyclical nature of existence. Integrating such perspectives would be akin to mixing poison with milk, undermining the tradition’s integrity under the misguided notion that “anything goes.” As the principle of tolerance does not extend to tolerating or accepting the intolerant, Hindutva’s inclusivity has its limits.

This delineation is not about exclusion for its own sake but about preserving the coherence of Hindutva’s spiritual identity. The tendency among some modern Hindus to adopt an overly permissive mindset risks diluting Hindutva’s distinctiveness, a concern echoed in contemporary discourse. Hindutva’s diversity-of-unity flourishes within its traditions, allowing varied expressions to converge under a shared metaphysical canopy. Extending this pluralism and inclusivity beyond these boundaries risks being self-destructive, necessitating a clear reaffirmation of limits to safeguard Hindutva’s integrity.

Conclusion

A Hindu is defined by their adherence to the core principles of Hindutva (Sanatana Dharma), namely belief in karma (the law of cause and effect), punarjanma (the cycle of rebirth), rta (the cosmic order sustaining existence), and purushārtha (the fourfold goals of life: artha, kāma, dharma, and moksha). These principles form the bedrock of a universal spiritual framework of Hindutva that transcends geography, culture, and time, uniting diverse practices — whether bhakti, jnāna, yoga, tantra, Vedic chants, devotional worship, nature worship, or ancestor veneration — under a shared metaphysical vision. A Hindu may follow any path or sect within this expansive tradition, while embracing the diversity-of-unity that characterises Hindutva. This framework not only preserves Hindutva’s pluralistic essence but also offers a timeless guide for ethical living, environmental stewardship, and spiritual liberation, relevant to both individual seekers and global challenges. However, this pluralism and inclusivity are bounded by Hindutva’s core principles, excluding theologies that fundamentally oppose its metaphysical foundations, such as the prophetic monotheism of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, or atheism and heterodoxies, to preserve its spiritual integrity. By rejecting colonial terminological distortions like “Hinduism” and affirming Hindutva as an indigenous synonym of Sanatana Dharma, Hindus reclaim an identity rooted in eternal truths, fostering a resilient, adaptive, and inclusive spiritual heritage that remains distinct yet universally accessible.

A very detailed and research based explaining in minute details.Thanks Garu.