Words are powerful—they weave together history, emotion, and identity. How we label cultural and spiritual traditions can either reflect their true essence or twist it into something unrecognizable. This is especially clear when we look at Santana Dharma, the ancient spiritual tradition often called “Hinduism”—a name born from colonial influence. In contrast, “Hindutva” arose as a native effort to recapture a richer sense of religious, cultural, and civilizational identity. So, what do these terms signify, and why does their difference matter?

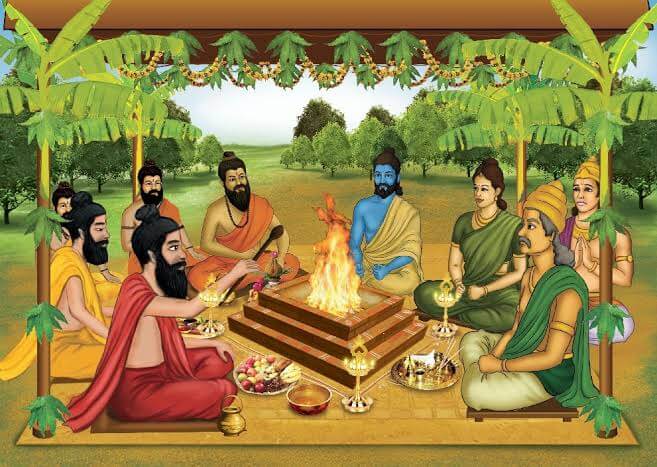

Santana Dharma, meaning “Eternal Way” or “Eternal Order,” is a spiritual tradition with roots reaching back millennia. It’s a vast, diverse system of beliefs and practices. Despite its profound diversity, this tradition was labeled “Hinduism” during British colonial rule. The term “Hinduism” is a hybrid of the Prakrit/Sanskrit word “Hindu” and the English suffix “-ism,” which suggests an organized religion akin to Christianity or Islam. It is a colonial shorthand that glossed over the rich complexity of Santana Dharma. As a result, “Hinduism” became a convenient but reductive label, much like calling a sprawling, vibrant ecosystem a “garden” for the sake of simplicity.

To understand the emotional and cultural weight of terms like “Hinduism” and “Hindutva,” consider the distinction between “home” and “house.” A “house” is a physical structure—neutral, functional, and devoid of personal meaning. “Home,” however, evokes warmth, belonging, and family. The difference lies in connotation: while both words refer to a place of residence, “home” carries a deeper, more personal resonance.

Also Read:

The Eternal Debate: Who is more powerful Lord Shiva or Lord Vishnu?

Scientific benefits of chanting Om

Similarly, “Hinduism” feels like the “house”—a detached, outsider’s term imposed by colonial powers. It describes the tradition but strips it of its lived-in, cultural depth. “Hindutva,” by contrast, aims to be the “home”—a term that resonates with identity, heritage, and a sense of belonging. This analogy highlights how language can either alienate or empower, depending on who wields it and for what purpose.

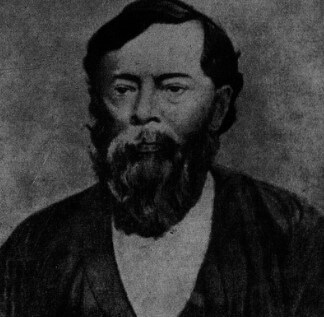

While “Hinduism” is a colonial construct, “Hindutva” emerged as an indigenous response. The term Hindutva was coined by Chandranath Basu in the late 19th century and means “Hindu-ness”. A prolific author, Basu wrote many works, but used the term “Hindutva” for the first time in Hindutva: Hindur Prakrita Itihas (1892). Hindutva represents a rejection of external labels and a return to indigenous roots. It carries a deeper connotation than “Hinduism,” aligning with the idea of shedding imposed terms to reclaim control over self-definition.

Naming is more than a practical act—it’s a statement of power. When a community is labeled by others, it can feel like losing a piece of itself. Santana Dharma, with its timeless truths and many paths to the divine, existed long before the colonial tag of “Hinduism” tried to box it in. Choosing terms like “Hindutva” can be a way to take back that power. The divide between “Hinduism” and “Hindutva” shows how language shapes identity: one term simplifies and alienates, while the other seeks to restore depth and ownership.

The distinction between “Hinduism” and “Hindutva” reveals the profound impact of language on identity. “Hinduism,” with its colonial roots, began as a simplification of Santana Dharma’s vastness, while “Hindutva” emerged as a response, seeking to reclaim a deeper religious, cultural and civilisational resonance.

In short, “Hinduism” carries the weight of a colonial past, reducing Santana Dharma to a shadow of itself, while “Hindutva” rings with a deeper religious, cultural and civilisational resonance reclaiming its voice. The distinction matters because it’s about more than words—it’s about who gets to tell the story.