The term ‘rare earth’ was coined in 1788 when a miner in Ytterby, Sweden, discovered an unusual black rock. The ore was called ‘rare’ as it had never been seen before and ‘earth’ because that was the 18th century geological term for rocks that could dissolve in acid. Despite being plentiful in the earth’s crust, rare earths are scattered throughout the globe, and not available in any quantity in one place.

Rare earths are a group of 15 elements in the periodic table known as the ‘Lanthanide series. These are categorized into Light Rare Earths (lanthanum to samarium) and Heavy Rare Earths (europium to lutetium). They are key enablers for technologies looking to lower emissions, reduced energy consumption, and improve efficiency, performance, speed, durability, and thermal stability. They are a key component for technologies that seek to make products lighter and smaller.

Rare earths react with other metallic and non-metallic elements to form compounds each with specific chemical behaviour. This makes these elements indispensable and non-replaceable in many electrical, optical, magnetic, and catalytic applications.

Rare earth elements (REE) are relatively plentiful in the earth’s crust, however, because of their geochemical properties, usually dispersed. This means they are not found in concentration to make them viable to mine. It is this scarcity that has led to them being classified as rare earths.

Rare Earth Availability

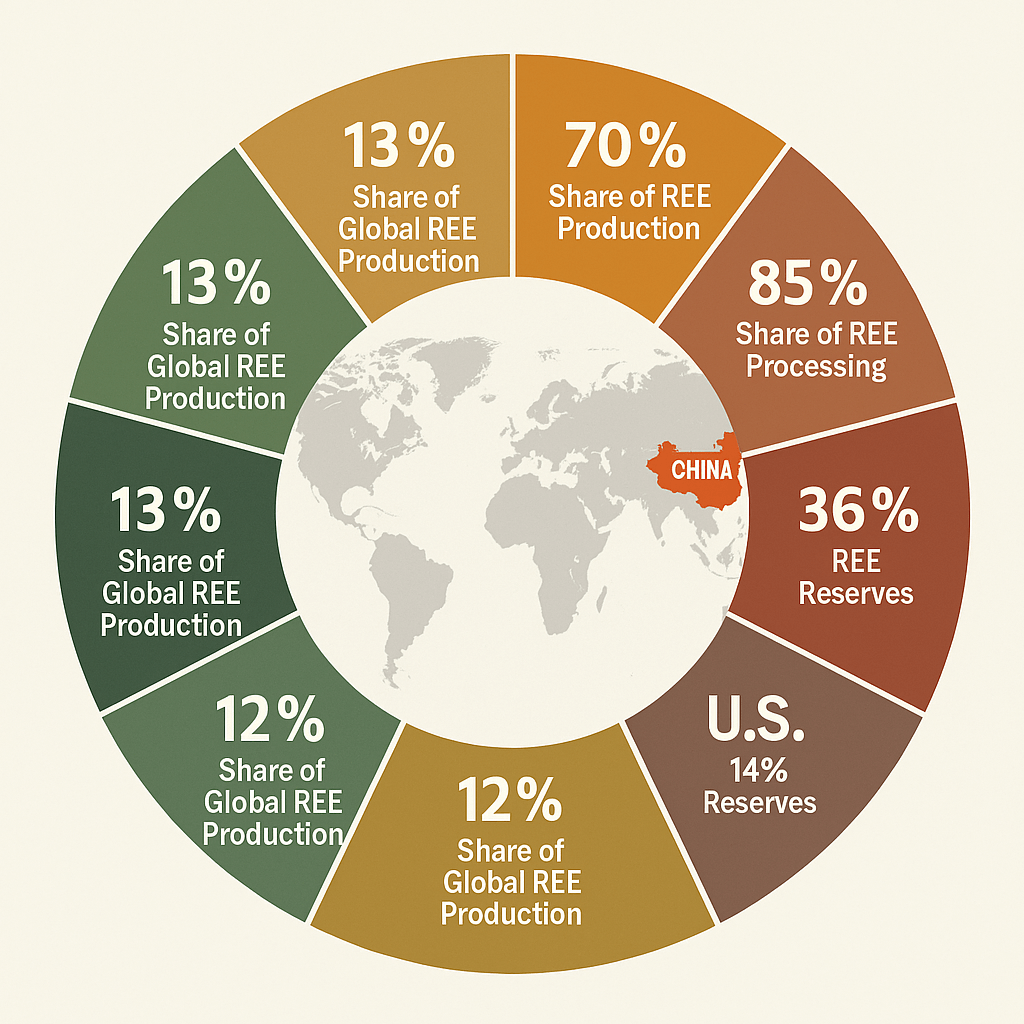

Global rare-earth reserves are estimated to be roughly 120 million metric tons of ‘rare-earth oxide’ equivalent, of this China alone controls about 49% of known deposits. China also produces 69.2% of global rare-earth output and commands 85% of global separation and refining capacity. This concentration of resource and production allows China to exert global leverage.

India, by contrast, holds third-largest rare-earth reserves (8.52 MMT) in the world. Unfortunate reality is that despite holding reasonable reserves it produces less than 1% of global output. This paradox—vast reserves but minimal production—defines India’s current predicament and presents a strategic opportunity. If adequately leveraged with coherent policy, technological investment, and effective use of its monazite assets, India can potentially transition from a marginal player to a leading rare-earth power within the next decade.

The Processing Bottleneck: Reserves Without Refining Capacity

The primary constraint on rare-earth supply is processing, not geology. Typical ore grades are below 5% REE content, meaning large volumes of rock must be mined and chemically treated. The flowsheet usually involves crushing, grinding, flotation, acid or alkali leaching, solvent extraction, and high‑temperature calcination, generating tailings that contain thorium and uranium. Managing these radioactive and chemical wastes to modern environmental standards is expensive and technically demanding.

China’s advantage lies precisely here. While it produces 69.2% of global rare-earth ore, it controls approximately 85% of global separation and refining capacity and an estimated 99% of heavy rare-earth processing for elements such as dysprosium and terbium. Even countries with sizeable reserves or growing mining output frequently ship concentrates to China for final separation and refining.

Vietnam provides a cautionary example. The decline in Vietnam’s extraction and production from 1,200 tons in 2022 to an estimated 300 tons in 2024 is primarily owing to technical hurdles, lack of advanced processing technology, low market prices driven by Chinese dominance, and domestic corruption crackdowns. Result, the global supply has tightened, even though geological endowment has remained unchanged.

For India, this presents a twofold problem. First, domestic processing capacity beyond basic monazite-to-oxide conversion is minimal. Second, the country has almost no domestic production of high‑performance permanent magnets, the highest‑value segment of the REE value chain. India presently imports nearly all of its advanced magnets, embedding strategic dependence into its defence industrial base.

REE Utility

Rare Earths are used in the manufacture of every day items – from smart phones to power steering and catalytic converters in cars. Rare earths are also used in futuristic applications such as robotics, home automation and green technologies to include hybrid and electric vehicles,wind turbines and superior magnets, etc.

In 2021, permanent magnets accounted for the largest share of global rare earth consumption. Neodymium rare earth magnets are the strongest type of permanent magnets , enabling high tech gadgets to become smaller, cheaper and lighter while maintaining optimal pull strength. Their superior magnetic quality has allowed designers to improve the efficiency of multiple technologies, such as hybrid and electric vehicles, mobile phones, televisions, computers, wind turbines, loudspeakers, aircraft controls, robots, and factory automation equipment. Ever wondered how manufacturers have been able to shrink your smartphone over the years? This is all on account of superior quality rare earth magnets used in these pholes.

Rare earths also helped to create colour TV. For many years, the rare earth elements yttrium and europium were used as phosphors to help us see colour red on tube televisions. Compounds of gadolinium and terbium were used to make yellow-green phosphors. Mixing very small amounts of these rare earth elements into the compound served to accentuate the colour on the screen, giving it a vivid quality that is today pleasing to the eyes.

These materials are indispensable for precision-guided weapons, advanced fighter jets, submarine propulsion systems, radar and sonar installations, electric vehicle (EV) motors, wind turbines, and consumer electronics. Their supply is concentrated in a handful of countries, their processing demands enormous environmental costs, and their extraction faces technological and regulatory barriers.

REE, also known as ‘green elements’ play a critical role in making green energy products. Driven by the world’s urgent need to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions, demand for rare earths will remain strong in the future as they are used to make a host of environmentally friendly products: from wind turbines, catalytic converters and hybrid cars to rechargeable batteries, energy efficient light bulbs and solar panels, etc. One of the biggest uses of rare earth metals in the world is in electric bicycles; rare earth magnets are lightweight and long range, allowing for efficient zero emission transport.

Defence Strategic Importance

Rare earths are labelled “strategic materials” because of (a) their geographic and processing concentration, (b) their irreplaceability in high-technology systems, and (c) their potential use as tools of geopolitical leverage. Substitution is technically possible in some low‑performance applications, but for precision-guided munitions, advanced radars, and high‑performance aerospace platforms, there are currently no cost‑effective alternatives that match REE-based magnets and materials.

Selected Defence Platforms and Approximate Rare-Earth Content

| Platform / System | Approx. REE Content | Key REE-Dependent Subsystems |

| F‑35 Lightning II fighter | ~418 kg | Radar, EW systems, targeting, flight‑control actuators |

| Virginia‑class submarine | ~4,600 kg | Propulsion, sonar arrays, combat systems, missile guidance |

| Precision-guided munitions | Few kg per missile | Fin actuators, seekers, IMUs |

| Air-defence radar systems | 1000 kg | Phased arrays, beam steering, signal processing |

Neodymium‑iron‑boron (Nd‑Fe‑B) magnets are central to these systems. They drive the small but powerful electric motors that actuate missile fins, aircraft control surfaces, turret drives, and guidance mechanisms. Dysprosium additions allow such magnets to function at elevated temperatures without demagnetising, a requirement for hypersonic weapons and jet-engine environments. Gadolinium and yttrium contribute to advanced radar and sonar signal‑processing components, while samarium‑cobalt magnets provide thermal stability for infrared-guided weapons.

China has already demonstrated a willingness to use its dominance as leverage. Export curbs during the 2010 Senkaku dispute and more recent controls on export of specific heavy rare earths during trade dispute with the United States, signal these materials can function as a “strategic weapons.” Between 2020 and 2023, 93% of yttrium compounds imported into the United States came from China, underlining the depth of dependency in even the most sophisticated global defence industrial base.

India’s Vulnerability and the Defence Imperative

India’s position is paradoxical: it is resource‑rich but capability‑poor. Despite its third‑ranked reserves, India’s production of around 2,600 tonnes per year is negligible in global terms, resulting in country almost entirely dependent on imported rare-earth permanent magnets. Flagship indigenous platforms—BrahMos missiles, Tejas fighters, INS Arihant‑class submarines, and Akash air‑defence systems—all incorporate critical subsystems that rely on foreign‑made REE magnets and materials.

Recognizing this, the Defence Ministry has begun planning a national strategic reserve of critical minerals, including rare earths, to buffer short‑term supply shocks. Rare‑earth mining projects have been reclassified as “strategic,” enabling faster environmental clearances under defence oversight. This represents an acknowledgement that materials security is now inseparable from national security.

India’s Unique Strategic Advantages

India also possesses advantages that few competitors can match. Monazite deposits along the coasts of Odisha, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, and Kerala contain significant thorium (6–8% by weight) as a co‑product. This aligns directly with India’s long‑standing three‑stage nuclear programme and BARC’s thorium‑fuel expertise, creating synergies between rare‑earth processing and the nuclear fuel cycle.

Because monazite is typically hosted in beach and dune sands, extraction can be conducted by surface mining and beneficiation of heavy‑mineral sands, rather than capital‑intensive underground mining. Combined with relatively low labour costs and a large domestic market for downstream products (EVs, renewables, defence), this offers a potential cost and scale advantage if environmental safeguards are properly integrated.

Policy Initiatives and Production Targets

The National Critical Mineral Mission (NCMM), funded at about ₹16,300 crore, envisages 1,200 exploration projects between 2024 and 2031, with rare earths as a central pillar. Complementing this is a Production Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme for rare‑earth permanent magnets, with an outlay of ₹7,350 crore and a target of tripling domestic magnet capacity by 2030. Both initiatives explicitly reference defence and clean‑energy applications, anchoring investment with assured offtake.

IREL has received Letters of Intent for three new mining blocks in Odisha, Andhra Pradesh, and Tamil Nadu, and the plan is to expand output from the present 2,900 tons per year to several thousand tons annually by 2030, with integrated oxide‑to‑magnet processing. If execution matches ambition, India can close much of the gap between its resource base and its industrial capability over the coming decade.

Global Market Opportunity and Commercial Drivers

The rare-earth market, though modest in absolute value by commodity standards, is expanding rapidly. Estimates place the market at roughly USD 3.74–5.14 billion in 2024, rising to USD 8.14–9.91 billion by 2032–2034, implying a compound annual growth rate of 8.6–10.2%. The drivers are clear: EV traction motors, wind‑turbine generators, industrial automation, consumer electronics, and defence modernization.

Demand for rare‑earth permanent magnets in EV motors alone is projected to nearly double by 2030 to about 100,000 tons per year. India’s domestic EV and renewable programs therefore provide a large anchor market for a future rare‑earth magnet industry, enhancing commercial viability of investments that simultaneously serve defence and civilian demand.

India’s Rare Earth Diplomacy: Strategic Engagements and Global Positioning

India’s rare earth diplomacy in 2024 represented a pivotal strategic shift, transitioning from heavy reliance on Chinese imports to diversified global sourcing and domestic processing capabilities. This multifaceted approach, driven by Khanij Bidesh India Ltd (KABIL) and aligned with the National Critical Mineral Mission Rare earth elements (REEs) have emerged as critical enablers of modern technologies, including renewable energy systems, electric mobility, advanced electronics, and strategic defence platforms. In this context, India has increasingly recognized rare earth diplomacy as a vital component of its broader economic security and geopolitical strategy. India’s approach combines international partnerships, multilateral engagements, and domestic capability enhancement to mitigate supply-chain vulnerabilities and reduce overdependence on dominant global suppliers.

Strategic Rationale

The global rare earth supply chain remains highly concentrated, with China controlling a significant share of mining, processing, and refining capacities. This concentration has underscored the geopolitical risks associated with supply disruptions and export controls. For India, which possesses notable reserves of light rare earths but limited processing infrastructure, diplomatic engagement has become essential to secure diversified and resilient supply chains.

Bilateral and Multilateral Engagements

India has pursued rare earth cooperation through strategic bilateral partnerships with resource-rich and technologically advanced countries. Collaboration with Australia focuses on exploration, mining, and downstream processing, leveraging Australia’s abundant reserves and India’s growing market demand. Engagements with Japan emphasize technology transfer, recycling, and advanced material development, reflecting Japan’s expertise in high-end rare earth applications.

At the multilateral level, India’s participation in the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue has expanded to include critical minerals cooperation. Within this framework, India, along with United States, Japan, and Australia, seeks to promote transparent, sustainable, and secure rare earth supply chains in the Indo-Pacific region. India has also engaged with ASEAN countries, particularly Vietnam, to explore joint ventures in rare earth mining and processing, thereby diversifying sourcing options and strengthening regional economic ties.

Role of State Institutions and Policy Alignment

India’s diplomatic initiatives are closely aligned with domestic institutional efforts led by Indian Rare Earths Limited and supported by policy frameworks such as the National Mineral Policy and the Critical Minerals Strategy. Diplomatic channels are increasingly used to facilitate overseas asset acquisition, joint research, and long-term offtake agreements, integrating foreign policy objectives with industrial development goals.

Strategic Implications

India’s rare earth diplomacy reflects a shift from a resource-centric outlook to a value-chain-oriented strategy. By integrating diplomacy with technology collaboration, sustainability standards, and supply-chain resilience, India aims to position itself as a credible and responsible stakeholder in the global rare earth ecosystem. Over the long term, such diplomatic engagement not only enhances India’s economic and strategic autonomy but also contributes to shaping a more balanced and multipolar global rare earth supply chain.

Strategic Vision: India’s Path to Number one position

India’s convergence of large reserves, favourable geology, monazite‑thorium co‑products, nuclear‑fuel expertise, large domestic market, and alignment with like‑minded partners creates a rare window of opportunity. The strategic priority is clear.

- Move up the value chain from ore and simple oxides to separated oxides, metals, alloys, magnets, and finished components.

- Link IREL and new private players to defence PSUs, EV and bind OEMs through long‑term offtake agreements.

- Use Quad and other partnerships to import processing know‑how while retaining sovereign control over resources and key stages of the value chain.

Conclusion

If India executes outlined agenda with both dedication and discipline, it can achieve rare‑earth self‑sufficiency largely for industrial use and defence by 2030. It can also become a net exporter of high‑value rare‑earth products and emerge as a reliable supplier in a world increasingly wary of single‑source dependency. For India, rare earths are not merely another mining opportunity; they are a cornerstone of India’s strategic autonomy and much needed leverage.