Few criminal cases in India’s recent memory have evoked such horror, disbelief, and outrage as the Nithari killings. The images of skulls and bones unearthed from the drains of Noida’s Sector 31 in December 2006 became etched in the national conscience. The case symbolized a grotesque mix of brutality and systemic decay a story of innocent children gone missing, an investigation marked by sensationalism, and a justice process tainted by procedural lapses.

But nearly two decades later, as the Supreme Court of India acquitted Surendra Koli once branded the “butcher of Nithari” the nation was compelled to confront another kind of horror: the realization that our criminal justice system, in its eagerness to deliver quick justice, may have compromised truth itself.

This case is no longer about one man’s guilt or innocence. It is about how a nation’s institutions investigative, prosecutorial, and judicial can stumble when driven by hysteria, pressure, and presumption rather than law, evidence, and fairness.

The Case Unfolds: Anatomy of Alleged Acts

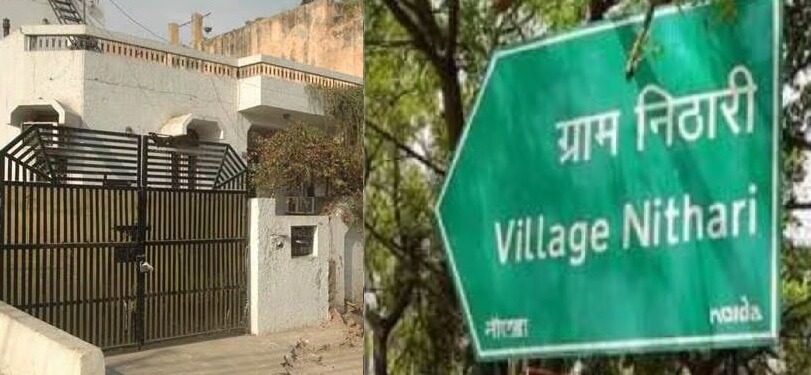

In late 2005 and 2006, residents of Nithari village adjoining Noida began reporting missing children mostly from poor families working as domestic help in the nearby upscale homes. Between 2005 and 2006, at least 19 children and several women were reported missing from the same locality. Police response was sluggish, routine, and indifferent until a 14-year-old girl named Payal went missing in December 2006.

Payal’s father, frustrated by police inaction, began his own search. His persistence led police to the residence of businessman Moninder Singh Pandher in Sector 31, where his domestic servant, Surendra Koli, worked. On 29 December 2006, skeletal remains skulls, bones, and personal items were discovered near the drain behind the house. The grisly find exposed a pattern of killings that shook the nation.

The Allegations

According to the police narrative, Surendra Koli lured young girls and women into the house under various pretexts, sexually assaulted them, murdered them, dismembered their bodies, and disposed of remains in the drain. The allegations even included acts of necrophilia and cannibalism claims that were never scientifically corroborated but amplified by sensational media reporting.

The alleged acts were horrifying enough to demand careful, meticulous investigation. Instead, what followed was a desperate attempt to close the case swiftly and produce culprits, regardless of procedural sanctity.

The Investigation: Media Pressure and Procedural Shortcuts

The Noida Police initially appeared clueless. Public outrage grew, the media storm intensified, and soon, the Uttar Pradesh Government handed over the investigation to the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI). The CBI arrested both Pandher and Koli, filed multiple charge sheets in different cases (each victim represented a separate FIR), and portrayed Koli as the principal offender.

However, from the outset, the investigation bore signs of haste and weakness:

- Lack of scientific linkage: The forensic evidence failed to conclusively link the recovered remains to specific victims or to establish Koli’s involvement through DNA matching or blood analysis.

- Reliance on confession: The central pillar of the prosecution’s case became Koli’s alleged “voluntary confession” under Section 164 of the CrPC recorded after nearly two months in continuous police custody.

- Public trial through media: Leaked details, exaggerated confessions, and gory reconstructions of the crime created a climate where conviction seemed the only acceptable outcome.

In reality, many of these so-called confessions were self-incriminatory statements extracted under duress, often without the presence of a lawyer or judicial satisfaction of voluntariness. Yet, they became the foundation of multiple death sentences.

Trial Court: Conviction and Death Sentence

Between 2007 and 2011, the Ghaziabad Special CBI Court conducted trials in multiple Nithari cases. In the first major case (Trial No. 611 of 2007), the Court convicted Koli under Sections 302 (murder), 364 (kidnapping), 376 (rape), and 201 (destruction of evidence) of the Indian Penal Code, sentencing him to death.

The reasoning leaned heavily on the confession and alleged recoveries from behind Pandher’s house. Pandher was acquitted in that particular case but convicted in some others on charges of conspiracy and abetment.

The trial court’s reliance on weak circumstantial evidence and disregard of procedural safeguards was striking. The guiding legal standard that circumstantial evidence must form a complete and unbroken chain pointing only to the guilt of the accused was stretched beyond recognition.

High Court: The First Layer of Judicial Endorsement

In 2009, the Allahabad High Court upheld Koli’s death sentence. While it expressed concern over certain inconsistencies, it concluded that the “heinousness of the act” warranted the “rarest of rare” punishment. The Court relied on Koli’s confession, treating it as voluntary, and on the recoveries, viewing them as corroborative of his guilt.

At this stage, the judicial system appeared united in its approach: the case was too gruesome to allow doubt. The presumption of innocence had silently given way to the presumption of guilt a pattern not uncommon in high-profile cases where public emotions overwhelm legal caution.

Supreme Court 2011: Confirmation of Death Penalty

In 2011, the Supreme Court affirmed the conviction and death sentence in Surendra Koli v. State of U.P. The Court echoed the lower court’s reasoning, describing the crimes as “brutal and beyond human comprehension.” It found no infirmity in the confession or recoveries, emphasizing the “gravity of offence” over procedural objections.

However, history would later reveal that the very evidence upheld in this judgment was riddled with constitutional violations including unlawful custody, coerced confession, and unreliable recoveries.

Years of Custody and the Shadow of Death

For more than a decade, Surendra Koli remained on death row. His mercy petitions moved through bureaucratic corridors in silence. In 2014, the Allahabad High Court commuted his death sentence to life imprisonment on the narrow ground of delay in deciding his mercy plea, not on merits of evidence.

Yet, multiple parallel trials against him continued, each based on similar confessional and circumstantial material.

High Court 2023: A Turning Point

In October 2023, a Division Bench of the Allahabad High Court acquitted Koli in twelve other Nithari cases. The Court undertook a deeper scrutiny of the evidence, identifying grave procedural and legal errors. Its findings were scathing:

- Confession not voluntary: Recorded after prolonged custody, without ensuring mental stability or legal counsel.

- Recoveries inadmissible: Made from open, publicly accessible areas; lacked exclusive knowledge or nexus to the accused.

- Forensic uncertainty: No DNA linkage conclusively connecting remains to the alleged victims or to Koli.

- Judicial complacency: The Magistrate recording the confession failed to ascertain voluntariness as mandated under Section 164(4) CrPC.

The High Court observed that “the entire case rested on statements and recoveries which could not pass the test of fairness or reliability.”

This judgment exposed the fragile foundation of the Nithari prosecutions and paved the way for the Supreme Court’s eventual intervention.

Supreme Court 2025: The Final Acquittal

On 11 November 2025, the Supreme Court of India finally acquitted Surendra Koli in his last pending case. The Bench held that once the High Court had disbelieved the same evidence in twelve other cases, maintaining a conviction in one case would amount to a violation of Articles 14 and 21 equality before law and right to life and personal liberty.

The Court meticulously dissected the flaws in the investigation and prosecution:

(a) Confessional Statement

The confession was inadmissible as it was extracted after prolonged custody, with no judicial inquiry into voluntariness. The magistrate’s mechanical certification without probing the accused’s condition violated the procedural safeguards of Section 164 CrPC.

(b) Recovery Evidence

The Court found the recoveries unreliable the alleged sites were already known to police and the public. There was no contemporaneous record proving the accused’s exclusive knowledge. The so-called discoveries were therefore legally irrelevant.

(c) Constitutional Violations

By sustaining a conviction on discredited evidence, the State had violated the fundamental principles of equality and fairness. The Court held that “suspicion, however grave, cannot substitute proof beyond reasonable doubt.”

With these observations, the Supreme Court ordered Koli’s immediate release, marking the end of nearly two decades of incarceration.

The Law Behind the Lessons

The Supreme Court’s reasoning in the Nithari case reaffirms several timeless principles of criminal jurisprudence:

(i) Voluntariness of Confession

Under Section 164 CrPC, a confession must be recorded only if the Magistrate is satisfied that it is made voluntarily. Any hint of inducement, threat, or prolonged custody vitiates it. The Koli case exemplifies the danger of treating coerced statements as confessions.

(ii) Proof Beyond Reasonable Doubt

The golden thread running through criminal law as reaffirmed in Sharad Birdhichand Sarda v. State of Maharashtra is that guilt must be established beyond reasonable doubt. The Nithari investigation substituted forensic science with sensational storytelling, diluting this principle.

(iii) Equality Before Law

Article 14 demands uniform treatment. When the same evidence is rejected in multiple cases but accepted in one, the disparity becomes unconstitutional a precedent the Supreme Court has now corrected.

(iv) Protection of Life and Liberty

Article 21 embodies the essence of fair procedure. The Court has consistently held that fairness is not a privilege; it is the essence of justice. The Nithari verdict is therefore as much a reaffirmation of due process as it is a correction of past excesses.

Systemic Failures: A Mirror for the Criminal Justice System

The Nithari saga is not merely about individual error; it is a reflection of systemic dysfunction across institutions:

A. Investigative Myopia

The pressure to “solve” the case led investigators to chase confessions rather than corroborate evidence. This culture of performance-based investigation where the number of solved cases matters more than the quality of proof is the root cause of many miscarriages of justice.

B. Judicial Passivity

Trial courts often function as conveyor belts of police theory rather than constitutional guardians. In the Nithari trials, the judiciary’s failure to interrogate procedural irregularities allowed a narrative to masquerade as evidence.

C. Forensic Deficiency

Despite advances in technology, forensic processes remain fragmented, underfunded, and unaccountable. The lack of DNA match confirmation and poor chain-of-custody documentation in this case demonstrate how weak science can undo strong suspicion.

D. Media and Public Pressure

Public outrage, while understandable, cannot dictate investigation. The media’s portrayal of Koli as a “serial killer” before trial ensured that objectivity was lost. Investigators and judges, consciously or subconsciously, responded to that sentiment.

E. Custodial and Legal Aid Neglect

Extended police custody without independent counsel contradicts the constitutional principle of humane treatment. Koli’s prolonged isolation and denial of counsel reveal how easily the system can bypass basic rights in the name of expediency.

Lessons for Investigators, Prosecutors, and Judges

Every stage of the Nithari case teaches a vital lesson:

- For Investigators: Evidence is built through science, not supposition. Confession is not proof it is merely one piece of the puzzle, valid only if free and voluntary.

- For Prosecutors: Their duty is not to secure conviction but to ensure justice. Presenting tainted evidence knowingly is an ethical failure.

- For Magistrates and Judges: Recording a confession is a constitutional act, not an administrative formality. They must probe, not presume, voluntariness.

- For Policymakers: Criminal justice reform is not about new laws but about enforcing the spirit of existing ones fairness, equality, and accountability.

Reform Imperatives

The Nithari verdict must catalyze introspection and reform. Key steps include:

- Mandatory Video Recording of all confessions and custodial interrogations.

- Independent Legal Counsel for accused persons from the moment of arrest.

- Forensic Oversight Authority to ensure scientific integrity in evidence collection.

- Judicial Training on confessional law and the psychology of coercion.

- Accountability Mechanisms for officers and magistrates who violate procedural safeguards.

These measures would ensure that justice is not only done but demonstrably seen to be done.

Conclusion: Justice as Discipline

The Nithari case stands as both tragedy and lesson. For the families who lost their children, justice remains incomplete. For the system that punished without proof, it is an indictment. And for society, it is a reminder that when law yields to pressure, everyone loses.

As one who has served in uniform and later in the courts, I have seen justice as both discipline and conscience. The Nithari verdict is not a failure of law it is a failure to follow it. If this judgment rekindles in our officers, prosecutors, and judges the humility to question, the courage to verify, and the discipline to act lawfully, then perhaps those nameless children of Nithari will not have died entirely in vain.

Justice is not vengeance. It is the pursuit of truth through fairness. And that pursuit demands from every guardian of the law restraint, integrity, and compassion.

Your extremely well articulated article reminded me to the false espionage case of Nambi Narayanan, ISRO scientist harassment case. 1994 espionage case against scientist Nambi Narayanan, who was falsely accused and arrested in a case that was later deemed fabricated by the CBI and the Supreme Court. The case involved accusations of espionage, but the investigation was found to be flawed, leading to the arrest and torture of Narayanan and other scientists.

Accusations: The case began with allegations that confidential documents related to India’s space program were leaked to foreign powers.

Arrests: Nambi Narayanan, a prominent scientist, was arrested along with other ISRO officials and individuals, including a Maldivian national.

False charges: In 1996, the CBI filed a closure report, stating the case was fabricated and not a real espionage incident. The Supreme Court later endorsed this finding, calling the police action “psycho-pathological treatment” that jeopardized Narayanan’s liberty and dignity.

Torture: Nambi Narayanan and others reported being tortured by police and intelligence officials during their interrogation.

Outcome: After a long legal battle, Narayanan was exonerated. He was awarded compensation, and the Supreme Court also indicated that authorities responsible for the harassment should face consequences. However, the case had a devastating impact on his career and life, as he retired without achieving his goals in the field of cryogenic propulsion.

Very well articulated. There is an urgent need to highlight and attention to the issue projected by writer