Sanskrit as India’s Official Language

While Palagummi Sainath’s claims about Hindi’s history are inaccurate, his critique of Hindi’s dominance inadvertently highlights a more profound issue: the choice of Hindi as India’s official language over Sanskrit. Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, a key figure in the making of India’s Constitution, proposed Sanskrit as the official language of the Union through an amendment submitted on September 10, 1949, in the Constituent Assembly, as reported by The National Herald and supported by 16 signatories, including T.T. Krishnamachari and Dakshayani Velayudhan from non-Hindi-speaking regions. Although Ambedkar did not actively move or debate this amendment, his proposal, as noted by scholars like Granville Austin, likely reflected a strategic response to the contentious Hindi-English language debate, suggesting Sanskrit’s neutrality as a potential unifier across India’s linguistic diversity. Some, including former Chief Justice Sharad Bobde, interpret this as recognition of Sanskrit’s capacity to foster national unity and revive India’s civilisational heritage, given its historical role as a link language in ancient scholarship. By prioritising Hindi, India missed a historic opportunity to harness Sanskrit’s unparalleled depth, breadth, and vitality to address challenges in education, culture, and national identity.

Sanskrit is not merely a language; it is the bedrock of Hindu civilisation as it has been the medium of India’s philosophical, scientific, literary, and spiritual achievements. The Vedas, Upanishads, Mahabharata, Ramayana, Bhagavad Gita, and texts like Panini’s Ashtadhyayi, Aryabhata’s mathematical treatises, and Kalidasa’s dramas were all composed in Sanskrit. These works represent a corpus of knowledge that spans metaphysics, linguistics, mathematics, astronomy, medicine, and aesthetics, unmatched by any other language in its scope and precision. Sanskrit’s grammatical structure, with its highly systematic rules codified by Panini, is considered a marvel of human intellect, capable of expressing complex ideas and subtle nuances with unparalleled clarity.

Also Read: Hindi, Sanskrit, and the missed opportunities -1

Sanskrit’s role as a link language in ancient India is equally significant. It was the medium of scholarship and communication among elites across regions, from Taxila to Kanchipuram, transcending linguistic diversity. Unlike Hindi, which is associated with northern India and faces resistance in the South, Sanskrit is a neutral language with no regional bias, making it an ideal candidate for national unity. Its sacred status further enhance its cultural legitimacy as a unifying force.

By declaring Sanskrit as the official language, India could have revitalised its education system, which currently grapples with linguistic fragmentation and a colonial legacy. English dominates higher education, creating a linguistic elite and alienating millions who lack access to quality English-medium schooling. Hindi, while widely spoken, lacks the technical vocabulary, linguistic depth and academic rigor needed for advanced disciplines. Sanskrit, with its vast corpus of technical texts and its ability to generate new terms (as demonstrated in modern Sanskrit lexicography), could have served as a robust medium for education across disciplines. For example, Sanskrit-based scientific terminology could have standardised technical education in a way that is both precise and culturally resonant, reducing reliance on English and empowering and enriching all Indian languages.

Moreover, Sanskrit education could have democratised access to ancient civilisational knowledge. Historical evidence suggests that Sanskrit was not exclusively an elite language; it was taught in Gurukuls and Pathashalas across India, accessible to students from various social strata. A national policy of Sanskrit education could have revived this model, fostering intellectual curiosity and cultural cohesion while enabling regional languages to draw from a common Sanskrit vocabulary pool.

Sanskrit’s revival would also have reinvigorated India’s cultural and spiritual vitality. The language’s decline, accelerated during colonial rule, coincided with a loss of confidence in indigenous knowledge systems. By prioritising Sanskrit, India could have reclaimed its philosophical heritage, fostering a deeper civilisational understanding. This cultural revival would have strengthened national pride and identity, countering the fragmentation caused by regionalism and linguistic politics.

Sanskrit as the Nourishing Mother of Indian Languages

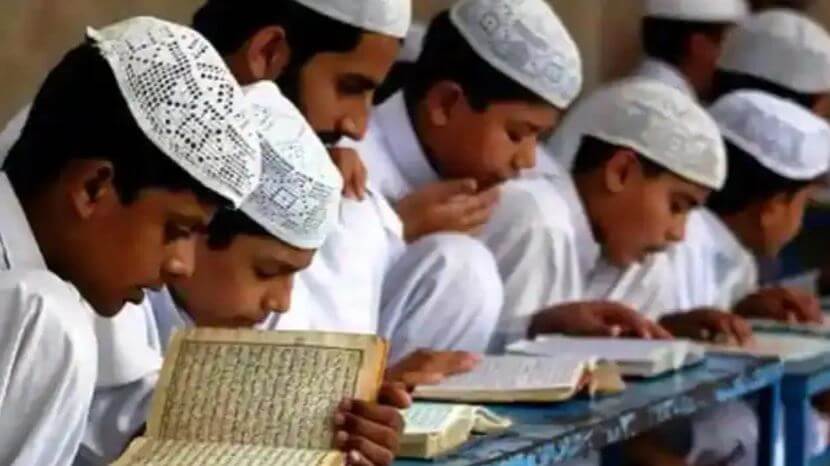

One of the most compelling arguments for adopting Sanskrit as India’s official language is its role as the mother and foster-mother of all Indian languages, including both Indo-Aryan and Dravidian ones. Sanskrit’s influence permeates the linguistic, literary, and cultural fabric of India, nourishing its diverse languages and providing a shared foundation for their growth. Had Sanskrit been declared the official language, all Indian languages, including Tamil, Telugu, Kannada, and Malayalam, would have flourished, enriched by their connection to a vibrant Indian tradition. Instead, the dominance of English as the undeclared official language of commerce, governance, and education is causing the decline of all Indian languages, with the notable exception of Urdu, which thrives due to institutional support from Muslim madrasa education and cultural reinforcement through Bollywood that produce Urdu movies which are labelled as Hindi.

As Sanskrit’s influence on all modern Indo-Aryan languages is direct, being their mother, they continue to draw heavily on Sanskrit for vocabulary except Urdu and those spoken outside India and Nepal. However, its influence on Dravidian languages, though less direct, is equally profound. Tamil, the oldest of the Dravidian languages, has an intimate relationship with Sanskrit. Tamil has absorbed thousands of Sanskrit loanwords over centuries, particularly in literature, religion, and administration. Tamil literature, including works like Tirukkural, Tolkappiyam, and Kamba Ramayanam, showcases shared indigenous traditions, themes, and vocabulary. Other Dravidian languages, such as Telugu, Kannada, and Malayalam, have even deeper Sanskrit connections, with up to 50–70% of their vocabulary derived from Sanskrit, especially in formal registers. This cross-pollination demonstrates Sanskrit’s role as a foster-mother, enriching Dravidian languages without erasing their distinct identities.

Had Sanskrit been India’s official language, it would have acted as a unifying force, providing a shared lexical and cultural reservoir for all Indian languages. A national Sanskrit-based education system could have standardised technical terminology across languages, enabling Hindi, Tamil, Bengali, and others to develop modern vocabularies rooted in Sanskrit strengthening linguistic cohesion while preserving regional diversity. Sanskrit’s neutrality, free from regional associations, would have mitigated tensions between Hindi and Dravidian languages, fostering collaboration rather than competition.

In contrast, the dominance of English has had a devastating impact on all Indian languages. As the language of commerce, education, governance, and social mobility, English has created a linguistic hierarchy where proficiency in English determines access to opportunities. This has led to a generational shift, with urban and semi-urban populations increasingly prioritising English over their mother tongues. Hindi, despite its official status, struggles to compete with English. Tamil, Telugu, and other Dravidian languages face similar challenges, with declining use in formal contexts and a shrinking literary output. In Tamil Nadu, for instance, English-medium schools are preferred, and Tamil is often relegated to informal communication, eroding its classical legacy. So is the case with all Indian languages. In other words, English has been destroying all Indian languages including Hindi and Tamil.

Ironically, Urdu is an exception to this trend, thriving due to unique cultural and institutional factors. Madrasa education, prevalent in Muslim communities, emphasises Urdu as a medium of religious and cultural instruction, ensuring its transmission across generations. Additionally, Bollywood, often mislabelled as a “Hindi” film industry, produces mostly Urdu films. Iconic dialogues, songs, and scripts draw from Urdu’s Perso-Arabic lexicon, popularised by Muslim writers like Sahir Ludhianvi and Javed Akhtar, keeping the language alive in popular culture. This mislabelling of Urdu as Hindi masks Urdu’s resilience, while Hindi itself struggles to maintain its literary and cultural depth in the face of English dominance.

The decline of Indian languages under English’s hegemony is not just a linguistic loss but a cultural tragedy. Language shapes identity, and the erosion of mother tongues disconnects Indians from their heritage, literature, and worldviews. Sanskrit, as the root of India’s linguistic tree, could have counteracted this trend by revitalising Indian languages through a shared civilisational framework. A Sanskrit-centric policy would have encouraged bilingualism in Sanskrit and regional languages, preserving diversity while fostering unity. For instance, Tamil could have continued its classical tradition while adopting Sanskrit-derived terms for modern contexts, as it did historically. All other languages would have similarly benefited, developing robust literary and technical registers without sacrificing their unique identities.

The failure to adopt Sanskrit has thus deprived India of a civilisational renaissance. English, as a colonial legacy, lacks the cultural resonance to inspire national pride or connect Indians to their civilisational roots. Its continued dominance threatens to turn Indian languages into relics of the past. Sanskrit, with its nourishing capacity, could have ensured their survival and growth, making India a model of linguistic pluralism rooted in a shared heritage.

The Consequences of Choosing Hindi Over Sanskrit

The decision to prioritise Hindi, formalised in India’s Constitution, was driven by political expediency rather than long-term vision. Hindi was seen as a practical choice, given its widespread use in northern India and its role in the nationalist movement. However, this choice, coupled with English’s dominance, has had several unintended consequences:

- Linguistic Tensions: Hindi’s promotion has been perceived as an imposition in non-Hindi-speaking regions, particularly in Tamil Nadu, leading to protests and demands for English or regional languages. Sanskrit, as a neutral language, could have avoided such conflicts.

- Educational and Cultural Disconnect: Ananda K. Coomaraswamy poignantly observed, “A single generation of English education suffices to break the threads of tradition and to create a nondescript and superficial being deprived of all roots—a sort of intellectual pariah who does not belong to the East or the West, the past or the future. The greatest danger for India is the loss of her spiritual integrity. Of all Indian problems, the educational is the most difficult and most tragic.” The choice of Hindi as India’s official language, despite its limited depth and breadth, and regional resistance, has driven many, including Hindi speakers, toward English-medium education, validating Coomaraswamy’s warning. This shift has deepened cultural disconnection and eroded India’s spiritual and intellectual heritage. Adopting Sanskrit as the official language could have unified the educational curriculum, providing a robust, culturally resonant framework while empowering and enriching regional languages, thus preserving India’s civilisational roots and fostering linguistic harmony.

- Lost Intellectual Potential: A nation ignorant of its past cannot chart its future. By marginalising Sanskrit, India has forsaken a language of unparalleled philosophical and scientific depth, severing ties to its civilisational roots. Sanskrit’s intricate grammar, exemplified by Panini’s Ashtadhyayi, inspires modern fields like artificial intelligence and linguistics, yet India fails to harness this extraordinary heritage. Embracing Sanskrit could have unleashed a renaissance of intellectual inquiry, positioning India as a global leader in knowledge creation while reclaiming its timeless legacy.

- All-Encompassing Linguistic Decline: The pervasive dominance of English across all domains is steadily extinguishing Indian languages, including Hindi and Tamil, with Urdu standing as a notable exception due to its sustenance through madrasa education and Bollywood’s Urdu films mislabelled as Hindi. Sanskrit, as the mother and foster-mother of all Indian languages, could have served as their vital lifeline, nourishing and revitalising both Indo-Aryan and Dravidian tongues like Tamil. By embracing Sanskrit, India could have secured the survival and vibrant flourishing of its linguistic diversity, preserving a rich cultural heritage against the overwhelming tide of English hegemony.

Dr. B.R. Ambedkar keenly perceived Sanskrit’s unmatched richness and versatility as the cornerstone of India’s civilisational revival. He recognised that no other Indian language rivalled Sanskrit’s ability to function as a medium for science, arts, law, governance, economics, and education, advocating it as a unifying force. By rejecting his proposal, the Constituent Assembly of India squandered a pivotal opportunity to restore the nation’s civilisational grandeur.

A Vision for Sanskrit’s Revival

Reviving Sanskrit as a vibrant, living language to anchor India’s cultural and intellectual identity is a transformative and achievable goal. Inspired by Israel’s successful revival of Hebrew, which transformed an ancient sacred language into a thriving national tongue, India can adopt a similar strategy to rejuvenate Sanskrit. A comprehensive plan, including the following key initiatives, is essential to make Sanskrit aspirational, accessible, and relevant to modern life while preserving its profound civilisational heritage.

Legislative Reform for National Cohesion: The foundation of this revival lies in bold legislative action. Amending the Constitution and the Official Languages Act of 1963 to establish Sanskrit as the official language of the Indian Union, replacing Hindi, would affirm its neutral and unifying role across India’s diverse linguistic landscape. This step would leverage Sanskrit’s historical role as a link language to foster national unity.

Transitioning to Sanskrit in Public Life: Within 10 years, governance, judiciary, legislature, commerce, and education should progressively shift to Sanskrit as the primary medium. Government officials, judges, lawyers, doctors, engineers, and other professionals should be incentivised to achieve Sanskrit proficiency within a set timeframe and use it in their professional activities.

Transforming Education: Education is the cornerstone of this vision. Establishing 1,000 Bharatiya Sabhyata Vidyalayas—Sanskrit-medium residential schools modeled on Navodaya Vidyalayas—would provide free, world-class CBSE education in Sanskrit. Accessible to students from all socio-economic backgrounds, these schools would immerse students in India’s ancient civilisational knowledge. Instruction in these schools would be in Sanskrit, with the mother tongue and English as compulsory subjects until the 12th grade, ensuring seamless transitions to English-medium higher education. Over 10 years, the number of Bharatiya Sabhyata Vidyalayas should grow to 10,000. Additionally, all Kendriya Vidyalayas should progressively transition to Sanskrit as the sole medium of instruction within 10 years, aligning with the broader goal of mainstreaming Sanskrit education.

To attract students and boost career prospects, these schools should offer free coaching for competitive entrance exams (e.g., medical and engineering) for 11th and 12th graders. Fully subsidised education through the postgraduate level, regardless of financial background, would make Sanskrit education an aspirational pathway.

Making Sanskrit Aspirational: To inspire widespread adoption, Sanskrit proficiency should be positioned as a prestigious skill that elevates social and economic status. Linking Sanskrit expertise to exclusive opportunities in government, academia, technology, and cultural industries, as well as business prospects in publishing, media, and heritage tourism, would drive enthusiasm. Competitive salaries, public recognition through awards and certifications, and corporate partnerships for Sanskrit-based innovations (e.g., AI language tools or cultural content) would create a self-sustaining cycle of learning and propagation.

Expanding Sanskrit in Higher Education: All higher education and scientific research institutions, including universities, colleges, and professional colleges such as medical, engineering, management institutes, should offer Sanskrit-medium courses. Graduates of these programs should receive preferential treatment in government employment, access to government contracts, and tax benefits, incentivising students to pursue Sanskrit-medium higher education and reinforcing its value in professional and economic spheres.

Translating Knowledge into Sanskrit: A national project should be launched to translate scientific, technological, legal, and academic texts from English into Sanskrit, enabling its use in modern disciplines. Additionally, all laws, rules, and regulations should be translated into Sanskrit to support its role in governance, judiciary, commerce and industry.

Employment Incentives: To promote Sanskrit education, 25% of government jobs should be reserved for individuals who have studied in Sanskrit medium at least up to the 12th grade, and another 25% for those educated in their mother tongue at the same level. Similarly, the private sector should be encouraged through tax benefits and other incentives to prioritise hiring candidates with Sanskrit-medium education up to the 12th grade, fostering broader adoption of the language.

Modernising Sanskrit’s Relevance: Integrating Sanskrit into higher education through innovative teaching methods and developing modern technical vocabulary would enable its use in science, technology, and other fields. Promoting Sanskrit through contemporary media, literature, and performing arts—such as modern Sanskrit films and music—would engage younger generations and embed the language in popular culture.

Leveraging Digital Tools: Digital innovation can democratise access to Sanskrit. AI-powered translators, online learning platforms, and mobile apps can make the language accessible globally. A Sanskrit academies should be established to coordinate research, education, and preservation efforts, providing a robust institutional framework for the revival.

Building Sanskrit-Speaking Communities: Community engagement is key to creating a living Sanskrit ecosystem. Inspired by Sanskrit-speaking villages like Mattur in Karnataka, initiatives to foster similar communities should be supported. Scholarships and employment opportunities tied to Sanskrit proficiency would encourage its practical use.

A Cultural Renaissance: This holistic strategy would revive Sanskrit and revitalise all Indian languages, including Hindi and Dravidian languages, which are not only stagnating but gradually fading. By offering a shared cultural and lexical foundation, Sanskrit would foster linguistic diversity while reinforcing India’s civilisational identity, paving the way for a vibrant cultural and intellectual renaissance rooted in its ancient heritage.

Overcoming Challenges Through Political Will

The success of this vision hinges on political will—where there is a will, there is a way; where there is none, obstacles loom large. Potential opposition, particularly from Dravidian parties in Tamil Nadu, can be addressed by declaring Tamil as the second official language of the Indian Union, ensuring inclusivity and mitigating regional concerns.

(Concluded)