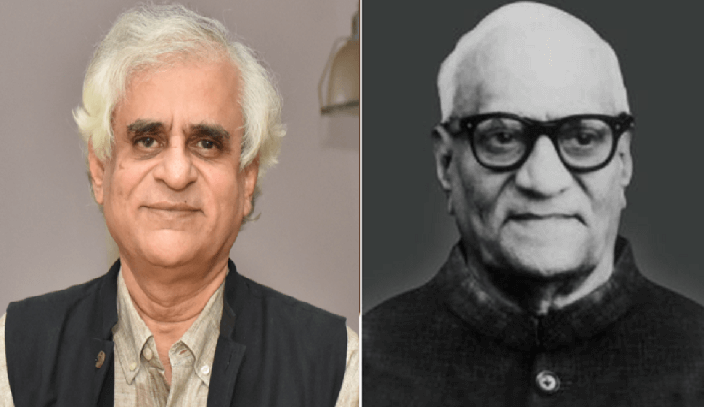

In a provocative statement, Palagummi Sainath, the grandson of former President of India V.V. Giri, claimed that Hindi is merely a 120-year-old language, pioneered singularly by Mahavir Prasad Dwivedi and that no great epics were written in it over the past 2,000 years because the language did not exist at that time.

Sainath further asserts that older languages like Bhojpuri are unjustly labelled as dialects of Hindi, dismissing Hindi’s historical depth. These claims, while intended to challenge the dominance of Hindi in India’s linguistic landscape, are rooted in a misunderstanding of Hindi’s evolution and its deep connection to India’s linguistic heritage.

However, Sainath’s critique inadvertently opens a broader and more significant discussion: the choice of Hindi as India’s official language over Sanskrit, a suggestion championed by Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, has deprived India of a unique opportunity to revive the vitality, robustness, and greatness of Hindu civilisation.

Sanskrit, as the civilisational language of India, possesses an unparalleled depth and breadth that no modern Indian language, including Hindi, can match. By prioritising Hindi and allowing English to dominate as the de facto language of governance, education, and commerce, India has not only missed the chance to rejuvenate its cultural heritage but also endangered the survival of its diverse linguistic traditions, except for Urdu, which thrives due to unique institutional and cultural support.

This article refutes Sainath’s claims with historical and linguistic evidence, while arguing that embracing Sanskrit as the official language could have nourished all Indian languages, including Dravidian ones, and revitalised India’s civilisational identity.

Refuting Sainath’s claims: The historical and Linguistic roots of Hindi

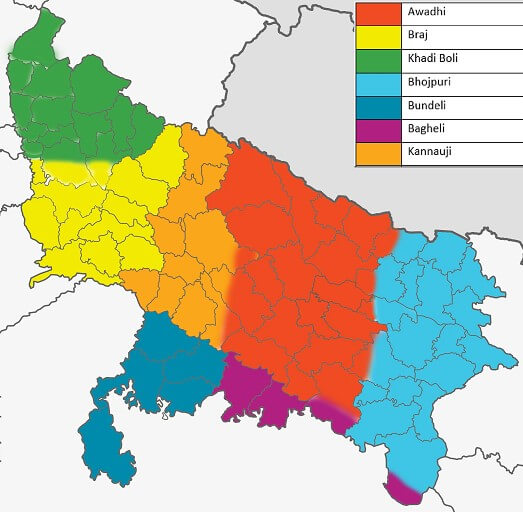

Sainath’s assertion that Hindi is only 120 years old and was singularly pioneered by Mahavir Prasad Dwivedi oversimplifies the complex evolution of the language. Hindi, as it is understood today, is a direct descendant of Sanskrit through Sauraseni Prakrit, a vernacular language that emerged around the 7th century CE in the Surasena region, corresponding to the modern Braj area of Uttar Pradesh and Rajasthan and adjoining parts of Delhi. Prakrits, including Sauraseni, were regional languages that evolved from Sanskrit, adapting their grammar and vocabulary to suit the needs of common people. Over time, Sauraseni Prakrit gave rise to Apabhramsa, a transitional stage that further evolved into Old Hindi, characterised by dialects such as Braj Bhasha, Awadhi, and Khariboli.

By the time of the Islamic invasions and the establishment of Muslim rule in northern India (circa 12th–13th centuries), the local Sauraseni Prakrit, or Old Hindi, was already a well-established medium of communication. Muslim rulers and their administrations adopted this language to interact with the local population, leading to the incorporation of Farsi, Arabi, and Turki (collectively referred to as FAT) vocabulary. This linguistic interaction gave rise to Urdu, a register of the same Hindustani language that retained the grammatical structure of Old Hindi but drew heavily on the FAT lexicon and adopted the Perso-Arabic script. Hindi, in contrast, continued to draw vocabulary from Sanskrit and was written in the Devanagari script. The distinction between Hindi and Urdu, therefore, is primarily one of vocabulary and script, not of grammar or syntax, as both share the same linguistic chassis rooted in Sauraseni Prakrit.

Sainath’s claim that Hindi did not exist 2,000 years ago is partially true in the sense that modern standard Hindi, based on the Khariboli dialect and standardised in the 19th century, did not exist in its current form. However, this ignores the continuity of its linguistic lineage. Old Hindi, in the form of Braj Bhasha and Awadhi, was the medium for significant literary works long before the 19th century. For example, Tulsidas’s Ramcharitmanas (16th century), written in Awadhi, and Surdas’s devotional poetry in Braj Bhasha are monumental contributions to Indian literature, often considered epics in their cultural and spiritual impact. These works, composed in dialects of Old Hindi, demonstrate that Hindi’s literary tradition predates Mahavir Prasad Dwivedi by centuries.

The evolution of languages is a natural process, with significant changes over time transforming their forms. For instance, modern English speakers often struggle to understand Shakespearean English, used just four centuries ago, due to shifts in vocabulary, grammar, and pronunciation, while Old English, influenced by Norman French after the 1066 Norman Conquest, is virtually unintelligible without specialised study. Similarly, Hindi’s evolution from Sanskrit through Sauraseni Prakrit and Apabhramsa reflects a dynamic linguistic continuum, with modern standard Hindi differing from its earlier forms like Braj Bhasha or Awadhi, yet retaining a clear lineage. This underscores that Sainath’s claim of Hindi being only 120 years old ignores the gradual transformation inherent in all languages, including Hindi’s deep roots in India’s linguistic heritage.

Dwivedi’s role, while significant, was not to “pioneer” Hindi but to standardise and modernise it. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Dwivedi, as the editor of the journal Saraswati, promoted Khariboli as the basis for modern standard Hindi, advocating for a Sanskrit vocabulary to distinguish it from Urdu’s FAT lexicon. This effort aligned with the nationalist movement’s push for a unified Indian identity, but it built upon an existing linguistic foundation. Sainath’s attribution of Hindi’s creation to Dwivedi alone dismisses the contributions of earlier poets, scholars, and the organic evolution of the language over millennia.

Sainath’s assertion that older languages like Bhojpuri are wrongly labelled as dialects of Hindi warrants closer examination. Linguistically, the distinction between languages and dialects hinges on mutual intelligibility, though sociopolitical factors often influence their classification. Bhojpuri, Maithili, Magadhi, Rajasthani, and other modern Indo-Aryan tongues, like Hindi, are Prakrits, vernaculars directly derived from Sanskrit. Even in ancient times, Pali, a Prakrit derived from Sanskrit, became a distinct language due to its reduced mutual intelligibility with other Prakrits, much like modern languages such as Bengali, Odia, and Marathi, which also trace their origins to Sanskrit. These Prakrits share a common Sanskrit origin, diverging over time through phonetic, morphological, pragmatic, orthological, and lexical variations. While Bhojpuri and Hindi exhibit significant mutual intelligibility, other Prakrits such as Marathi and Bengali are largely unintelligible to Hindi speakers, just as Hindi is to Marathi and Bengali speakers or those of other Prakrits, justifying their status as distinct languages. Historically, however, calling Bhojpuri a dialect of Hindi is not entirely inaccurate, as both are closely related Prakrits with shared grammatical and lexical features. Sainath’s objection to this classification appears more ideological than linguistic, reflecting resistance to Hindi’s perceived dominance rather than a nuanced analysis of its historical roots.

Historically, these Prakrits, encompassing both ancient forms like Pali and modern versions like Bhojpuri, Maithili, Magadhi, Braj, Rajasthani, Haryanvi, Himachali, Pahadi, Dogri, Kashmiri, Punjabi, Sindhi, Assamese, Nepali, Bengali, Odia, Chhattisgarhi, Konkani, Marathi, Gujarati, etc, were collectively referred to as apabhramsa, a term that highlights their linguistic evolution. Derived from the Sanskrit root bhramsha (to fall) and the prefix apa (away), apabhramsa literally means a “falling away” or deviation from a standard, often translated in linguistics as “corrupted” or “degraded” language. In linguistics, “corruption” denotes natural changes in a language—alterations in spelling, pronunciation, or vocabulary, including the incorporation of borrowed words or textual modifications that shift original meanings. While such changes are inherent to language evolution, the term apabhramsa implies a departure from the perceived “pure” or “correct” form of Sanskrit, the standard against which Prakrits were measured. This historical label underscores the shared linguistic framework of Prakrits, highlighting their interconnectedness despite their divergences. Sainath’s objection overlooks this complex continuum, where Prakrits, both ancient and modern, remain united through their Sanskrit lineage.

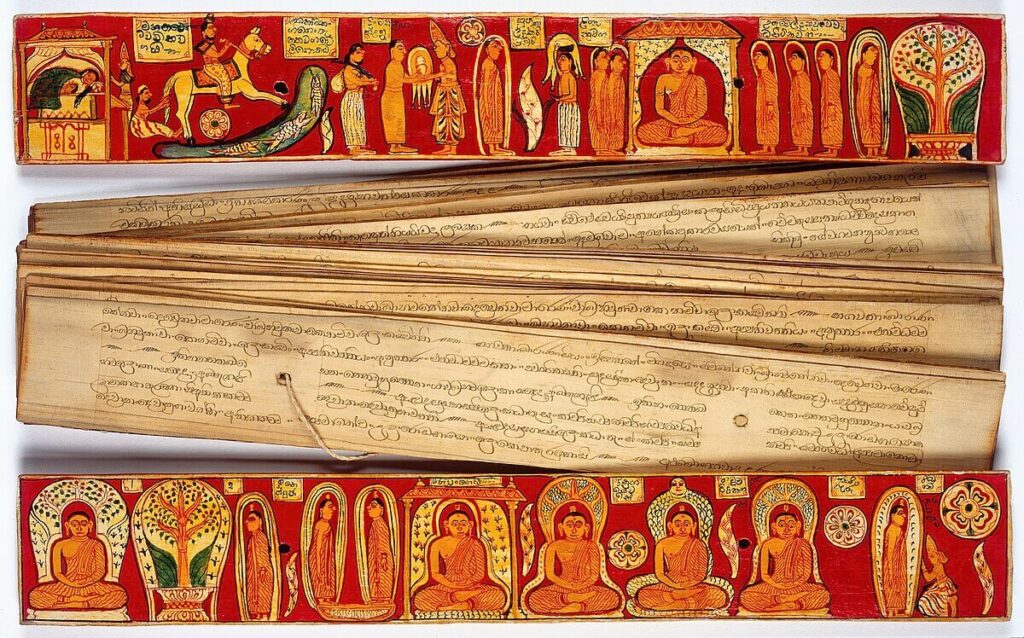

Sainath’s contention that no great epics were written in Hindi over the past 2,000 years, implying its non-existence, is both unreasonable and historically inaccurate, as it ignores the distinct roles of Sanskrit and Prakrits in Indian literary tradition. Classical epics, such as the Mahabharata and Ramayana, were composed in Sanskrit, the literary language of ancient India, while Prakrits, including the ancestral forms of Hindi, served as spoken vernaculars. This division is evident in Kalidasa’s plays, where Sanskrit is used for elevated discourse, but character-specific Prakrits reflect the colloquial speech of diverse social groups. Epics were thus not written in Prakrits. Even the Buddhist canonical literature in Pali, such as the Jataka tales, is largely rooted in a Sanskrit-influenced literary tradition, as it shares themes, motifs, and narratives with Sanskrit texts like the Panchatantra, Hitopadesha, and sections of the Mahabharata. Moreover, the Jataka tales and other Pali canonical texts, like the Buddhavamsa or Maha Parinibbana Sutta, do not constitute epics in the classical Sanskrit tradition of mahakavya, characterised by cohesive, expansive narratives like the Mahabharata, since they comprise diverse anthological collections of episodic tales, biographies, or doctrinal discourses. Nevertheless, Old Hindi, as a Prakrit, produced works of profound cultural and spiritual significance, such as Tulsidas’s Ramcharitmanas (16th century) in Awadhi and Kabir’s poetry in Braj Bhasha, which resonate with millions today, though these works are not epics in the Sanskrit. By alleging that Hindi’s lack of epics proves its recent origin, Sainath overlooks the historical linguistic context and literary tradition rendering his claim factually incorrect and reductive.

[…] Also Read: Hindi, Sanskrit, and the missed opportunities -1 […]