I have not become the King’s First Minister to preside over the liquidation of the British Empire

– Winston Churchill

History is a complex tapestry, woven from the threads of human decisions, circumstances, and the unpredictable currents of time. Yet, when examining figures like Winston Churchill and the British colonial era in India, we often fall into the trap of viewing them through a contemporary moral lens—stripped of the context that shaped their actions. This anachronistic judgment has fueled narratives that vilify Churchill and the British Empire while glossing over the intricacies of their roles in India’s past. A more balanced reassessment is overdue—not to absolve or exonerate, but to understand the motives, outcomes, and historical realities that defy simplistic caricatures.

Churchill’s Stance on Indian Independence: A Misunderstood Motive?

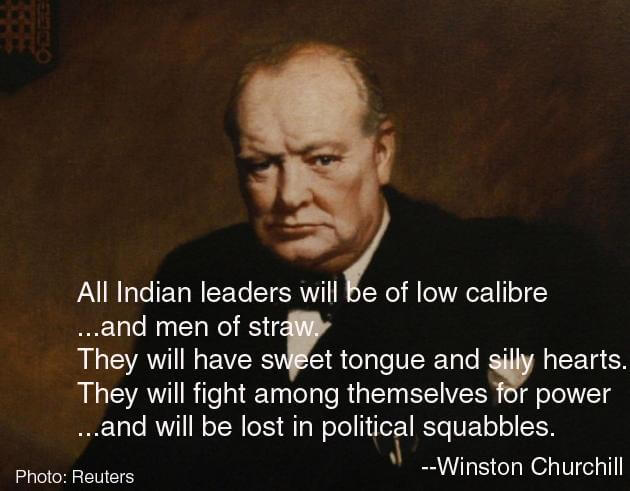

Winston Churchill’s opposition to Indian independence is frequently cited as proof of his imperialist arrogance or racial prejudice. His infamous 1942 remark calling Indian leaders “men of straw” and his warnings about the “Hindu-Muslim divide” tearing India apart are often framed as the rantings of a bigoted colonialist. However, this portrayal overlooks the broader context of his concerns. Churchill, an unabashed imperialist, saw the British Empire as a “civilising” force—a belief deeply rooted in the Victorian ethos of his upbringing. This perspective echoed Benjamin Disraeli’s depiction of India as “the brightest jewel in the Crown,” a symbol of British achievement and responsibility. To Churchill, retaining India wasn’t merely about power or profit; it was about preserving a system he genuinely believed brought order and progress to a subcontinent he viewed as fractious and ungovernable without external stewardship.

Consider the turbulent period leading up to India’s independence in 1947. Churchill argued—often with prescience—that a precipitous British withdrawal could unleash chaos. Clement Attlee’s Labour government, elected in 1945 amid Britain’s post-war exhaustion, prioritised a swift exit, driven by both economic necessity and a moral shift against imperialism. Churchill, however, feared that without a gradual transition, India’s deep-seated religious and social divisions would erupt into catastrophic violence. The Partition that followed, with its staggering toll—estimated at up to two million dead and fifteen million displaced—lends some credence to his apprehensions. Historical examples, such as the 1946 Calcutta riots, where over 4,000 perished in Hindu-Muslim clashes before independence, underscore the volatility he foresaw. The Noakhali riots later that year, which saw targeted violence against Hindus in Bengal, further highlight the communal tensions simmering beneath the surface. Could Churchill’s advocated phased withdrawal have mitigated the scale of this tragedy? While speculative, the question challenges the reductive narrative of Churchill as a heartless obstructionist. His stance, however flawed, reflected a pragmatic concern for stability rather than a blind lust for domination.

The British and India’s Historical Narrative: Myths and Misattributions

In post-independence India, the British have been cast as the arch-villains of the subcontinent’s story—a narrative heavily shaped by the country’s education system under Muslim leaders like Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, India’s first Education Minister. This portrayal often attributes India’s woes—famines, economic decline, and the Hindu-Muslim divide—solely to colonial rule, while downplaying the complexities of pre-colonial history. For instance, Will Durant, in his 1935 work, ‘The Complete Story of Civilisation: Our Oriental Heritage’, wrote, “The Mohammedan conquest of India is probably the bloodiest story in history. Islamic historians and scholars have recorded with great glee and pride the slaughters of Hindus, forced conversions, abduction of Hindu women and children to slave markets, and the destruction of Temples carried out by the warriors of Islam from 800 AD to 1700 AD. Millions of Hindus were converted to Islam by sword during this period.” He added, “It is a discouraging tale, for its evident moral is that civilisation is a precarious thing, whose delicate complex of order and liberty, culture and peace may at any time be overthrown by barbarians invading from without or multiplying within. The Hindus had allowed their strength to be wasted in internal division and war; they had adopted religions like Buddhism and Jainism, which unnerved them for the tasks of life.” This pre-colonial violence, whitewashed in modern Indian historiography by the Muslim-Marxist clique, contextualises the divisions the British later encountered—and exploited. Let’s examine some specific claims with greater scrutiny.

The Famines: Churchill and the Bengal Crisis

The Bengal Famine of 1943, which claimed between two and three million lives, is frequently laid at Churchill’s feet, with his alleged callousness epitomised by a supposed quip about Indians “breeding like rabbits.” Yet, the famine’s roots were multifaceted. Wartime disruption of rice imports from Burma (occupied by Japan in 1942), a devastating cyclone in 1942 that destroyed crops, and local administrative failures—such as hoarding by Indian merchants and inefficiencies in provincial governance—all contributed to the crisis. Churchill’s government, while not blameless, was stretched thin by the global demands of World War II and prioritised military needs over civilian relief in a distant colony—a cold, utilitarian calculus, but not a deliberate act of genocide. Earlier famines under British rule, such as the Great Famine of 1876–1878, which killed an estimated over five million, were exacerbated by laissez-faire policies that resisted state intervention.

Pre-colonial records, however, reveal frequent famines under Muslim rule, driven by policies like the zabt system’s fifty percent land taxes, forced labour, and constant warfare. These measures crippled farmers, ruined crops, and damaged irrigation systems. Muslim elites often hoarded grain, inflating prices during crises and prioritizing urban wealth over rural survival. Such policies contributed to devastating famines in 1344–1345, 1396–1398, 1630–1632, 1661, 1702–1704, and 1783–1784, which collectively killed over fifty millions, mostly Hindus, according to historical estimates. The suffering of Hindus, which aligned with Islamic theology’s disregard for non-Muslims (kafirs), left Muslim rulers unmoved. By the time the British arrived, India’s agricultural vitality had been significantly undermined in many regions, except in Hindu-ruled areas under Maharajas and Rajas, which often thrived. The colonial administration’s failures must be weighed against this longer history, not isolated as uniquely malevolent.

The Economic Myth: Wealth and Exploitation

Claims that India was the world’s first or second-largest economy before British colonisation—sometimes tied to Angus Maddison’s historical GDP estimates—require nuance. While the claim that India contributed roughly twenty four of global GDP in 1700 is definitely highly exaggerated, even this wealth was concentrated among elites, such as Mughal nobility and regional Nawabs rather than broadly distributed across the population, and in the regions under the Hindu rule. A stark contrast existed between the rich ruling Muslims and the impoverished Hindu masses. The debilitating Muslim invasions, beginning in the eighth century—including Mahmud of Ghazni’s plunder of Somnath in 1026 and the later Delhi Sultanate’s punitive taxation—devastated a once-flourishing Hindu economy, reducing much of the peasantry to subsistence. Regions under Hindu rule, such as the Vijayanagara Empire in the south, the Gajapatis in the east, and the Ahoms in the northeast, remained oases of prosperity into the sixteenth century. However, the idea of a uniformly thriving ‘Indian’ economy under Muslim dominion is a myth. The British did extract wealth through heavy taxation, the drain of resources via the East India Company, and trade imbalances—estimated by economist Utsa Patnaik to total $45 trillion in modern terms—but they also introduced transformative infrastructure: railways (over 40,000 miles by 1947), telegraphs, and a modern legal system. These developments, while serving colonial interests, laid the groundwork for India’s post-independence growth. The economic story is neither a golden age ruined nor a barren wasteland redeemed—it’s a mixed legacy of exploitation and modernisation.

The Partition: Roots Beyond British Rule

The narrative that the British “divided Hindus and Muslims” is the biggest ever lie in the entire world history invented by the Indian Muslim-Marxist clique. Islamic doctrine inherently views all non-Muslims, including Hindus, as adversaries who must be converted or eradicated until the entire world submits to Islam. Jihad, a continuous holy war against non-Muslims, including Hindus, has been waged on Hindus since the 8th century. The concept of two-nation theory, a separate Muslim nation and the demand for India’s partition originated with Sir Syed Ahmad Khan in 1888 at Meerut, not from British initiative. The British simply capitalised on the existing Muslim hostility toward Hindus to maintain their dominance. Far from orchestrating division, they made efforts until the last moment to avoid partition, aspiring to leave a legacy as India’s unifier. However, the unyielding stance of Muslims, bolstered by the Muslim League’s sweeping victory in the January 1946 elections and fueled by widespread Muslim support, coupled with gangsterism and massacres targeting Hindus, compelled the British to concede to India’s Partition and the establishment of Pakistan. Churchill, in his 1947 speeches, lamented the subcontinent’s breakup, having favoured a united India under a federal framework like the 1935 Government of India Act. Blaming the British obscures the agency of Islamic doctrines, Indian leaders and the pre-existing fissures they navigated.

Churchill in Context: Racist, Not Evil

Churchill was undeniably a product of his time—a Victorian imperialist who viewed non-European peoples through a paternalistic, often derogatory lens. His 1937 book Great Contemporaries reveals his admiration for order and hierarchy, while his speeches on India reflect an unshakable belief in British superiority. His 1899 comment in The River War, describing Sudanese tribes as “savage” yet “splendid,” mirrors his attitude toward Indians—condescending, yet not genocidal. Unlike Adolf Hitler, whose ideology centered on racial extermination, Churchill’s worldview was about preservation and control, not annihilation. His racism, while repugnant today, was typical of his class and era, shared by contemporaries like Rudyard Kipling.

Contrast this with his wartime leadership. Churchill’s defiance against Nazi Germany in 1940–1941, when Britain stood alone, saved Europe from tyranny—a feat that earned him global acclaim. His flaws don’t negate this achievement, just as his imperial stubbornness doesn’t make him a cartoonish villain. To judge him solely by 21st-century standards is to erase the historical air he breathed.

Rewriting the Narrative: A Call for Balance

India’s post-independence historiography, shaped by Islamic and leftist ideologies, has often whitewashed the brutality of pre-colonial Muslim invasions—such as Mahmud of Ghazni’s 17 raids between 1000 and 1027, which looted cities like Mathura, or the massacres under Tamerlane in 1398, which left Delhi in ruins—while amplifying British sins. This selective memory serves a political purpose but distorts reality. The British were neither saints nor demons; they were a colonial power navigating a complex land with both self-interest and a sense of mission, however misguided by modern lights.

Churchill, too, deserves reassessment. His love for the Empire was genuine, as seen in his 1953 lament, “I have not become the King’s First Minister to preside over the liquidation of the British Empire.” He was a towering figure of the 20th century—flawed, contradictory, and human. To understand him, and the British legacy in India, we must step beyond myths propagated by India’s Muslim-Marxist clique and into the messy truth of their time, embracing the full spectrum of history’s shades rather than painting it in stark black and white.

A wonderful article by Sri Nageshwar Rao well balanced and analysed.